The Fragmented Body: Mannequins and the Paris Exposition Internationale, 1937

By Paula Alaszkiewicz

DOI: 10.38055/FS050111

MLA: Alaszkiewicz, Paula. “The Fragmented Fashion Body: Mannequins and the Paris Exposition Internationale, 1937.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-28, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050111.

APA: Alaszkiewicz, Paula (2024). The Fragmented Fashion Body: Mannequins and the Paris Exposition Internationale, 1937. Fashion Studies 5(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050111

Chicago: Alaszkiewicz, Paula. “The Fragmented Fashion Body: Mannequins and the Paris Exposition Internationale, 1937.” Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2024): 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050111.

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 1

Keywords

Mannequins

International exhibition

Fragmentation

Subjectivity

Interwar

abstract

Mannequins are pivotal to the creation and communication of meaning in fashion display. Despite changes in materials and design, throughout much of their history mannequins have perpetuated a standardized, restrictive, and harmful ideal of the fashion body. This article contributes to the limited scholarship on mannequins by analyzing an unusual example of modern mannequin design: the figures debuted in the Pavillon de l’Élégance at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, held in Paris in 1937. With a lack of facial features, anatomically impossible proportions, and poses suggestive of tension and terror, these mannequins clearly depart from conventions of bodily containment and serene elegance. This vision of the fashion body belongs to a broader cultural preoccupation with fragmentation seen in the arts and visual culture. It also materializes developing psychoanalytic ideas of fragmentation and subjectivity, namely those put forth in Jacques Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage (1936). The fragile and fragmented mannequins reflect a body and associated model of subjectivity rooted in instability. As such, they counter assumptions that fashion provides a means to stabilize the body and subjectivity. Drawing on original archival research and methods of art history, this article presents these unconventional mannequins as reflections of their unique historical and cultural conditions, when the traumas of recent war intersected with the foreboding premonition of the horrors that would soon unfold.

Amongst the scenographic columns, balustrades, and amphorae scattered like archaeological relics in the winding corridors of the fashion pavilion at the Paris Exposition Internationale (1937), luxurious couture garments were displayed on mannequins cast from a pale pink plaster intended to convey terracotta (Figure 1). The mannequins were designed by the French sculptor Robert Couturier. With a complete lack of facial features, disproportionate limbs, and dramatic poses suggestive of torment and terror, the mannequins reject the idealized, passive, contained femininity perpetuated in interwar mannequin design. Instead, they present a body that appears to be dissolving or coming undone.

This article seeks to remedy the surprising lack of scholarly attention directed towards this unconventional expression of the fashion body. Employing original archival research and art historical approaches wherein images provide primary evidence, I situate the mannequins within the unique cultural context of the Exposition Internationale. The event occurred on the eve of the Second World War during a period marked by anxieties around bodily wholeness. Images of bodily fragmentation linked to the fresh traumas of war proliferated in interwar art and visual culture. At the same time, bodily fragmentation was being theorized in relation to subjectivity in the psychoanalytic work of Jacques Lacan.

Figure 1

Photograph of the Haute Couture Section of the Pavillon de l’Élégance at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris, 1937 published in “Le Pavillon de l’Élégance,” Art et décoration: Revue mensuelle d’art moderne, 1937, Tome LXVI, 246, Gallica – Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

With an insistence on bodily instability, the mannequins embody a model of subjectivity that denies wholeness, thereby providing a significant — albeit short-lived — counterpoint to prevailing accounts of the design and role of the fashion mannequin.

The Surrogate Fashion Body

Since the mid-eighteenth century, mannequins have served as indispensable tools of fashion production, and later, display and retailing. As a proxy for the human body, the mannequin is central to how meaning is made and communicated in fashion. With ever-changing materials and designs, the mannequin also operates as a “conveyor of a contemporary attitude.” [1] Mannequin design evolves in concert with changing social, gender, and bodily ideals, as well as fashionable silhouettes, trends in retailing, and broader movements in art and design. Such changes are documented in historical overviews of the mannequin, including those authored by Nicole Parrot (1982), Sara K. Schneider (1995), and Emily Orr (2015), which chart the various ways in which the human body has been reproduced in three-dimensional form to facilitate the manufacturing and promotion of fashionable dress.

Tailors and dressmakers have relied on body forms since the mid-eighteenth century, lest their clients be subjected to endless fittings.[2] As Alison Matthews David argues, the development of the fashion mannequin (especially the female mannequin) for display purposes is bound up in the many transformations to the Euro-American fashion system occurring in the mid-nineteenth century, including the “mass production, standardization, and literal dehumanization of clothing production and consumption.” [3] As the mannequin came to occupy the dazzling windows and salesfloors of new department stores, manufacturers utilized smooth wax “skin,” glass eyes, and human to hair in pursuit of a “lifelike” surrogate of the human body. However, in mannequin design, “anatomical perfection [is] not to be confused with accuracy.” [4] Modern mannequin design simultaneously idealizes and standardizes the human form. As a result, a restrictive ideal of a white, thin, tall, able-bodied woman bedecked in the latest fashions became the enduring normative fashion body. By using mimesis, or a “realistic” style, modern mannequin design effectively naturalized this highly constructed ideal. In this regard, mannequin design perpetuates the myth of “realism” within the arts as a “‘styleless’ or transparent style, a mere simulacrum or mirror image of visual reality.”[5]

[1] Emily Orr, “Body Doubles: A History of the Mannequin,” in Ralph Pucci: The Art of the Mannequin (New York: Museum of Arts and Design, 2015), 37.

[2] Alison Matthews David, “Body Doubles: The Origin of the Fashion Mannequin,” Fashion Studies, 1, no. 1 (2018): 11, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010107.

[3] Matthews David, “Body Doubles,” 1.

Since the 1970s, the museum exhibition has become an increasingly prevalent forum for the dissemination of contemporary fashion.

The eerie absence of the body, and thus, of meaning and context, in museum exhibitions has been noted in numerous formative texts.[6] Curators have confronted the problem of the ghostly mannequin with various experimental solutions, including period styling, wigs, and even projected faces that blink, smile, and speak.[7] Yet, curators must also direct their efforts to the dismantling the white, elongated, able-bodied woman as the de-facto surrogate fashion body. As Chloe Chapin, Denise N. Green, and Samuel Neuberg have demonstrated, the static nature of the standard mannequin is incapable of reproducing gender and other intersections of identities.[8] The process and outcome of the mannequins designed for Africa Fashion (2022) set an important precedent for institutions that have the resources to commission bespoke mannequins.[9] Meaningful strategies for smaller institutions, such as university collections, to contend with the lack of representation in existing mannequins have been outlined by Dyese L. Matthews and Kelly L. Reddy-Best (2022).

[4] Alana Staiti, “Real Woman, Normal Curves, and the Making of the American Fashion Mannequins, 1932-1946,” Configurations 28, no. 4 (2020): 407.

[5] Linda Nochlin, Realism (Harmonsworth: Penguin, 1971), 14.

[6] See, for example, Elizabeth Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: Virago, 1985), 1; Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 10; Lou Taylor, The Study of Dress History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 24.

[7] See, Julia Petrov, “The Body in the Gallery: Revivifying the Historical Fashion,” in Fashion, History, Museums: Inventing the Display of Dress (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 137-66 and Ingrid Mida, “Animating the Body in Museum Exhibitions of Fashion and Dress,” Dress 41, no. 1 (2015): 37-51.

[8] Chloe Chapin, Denise N. Green, and Samuel Neuberg, “Exhibiting Gender: Exploring the Dynamic Relationship between Fashion, Gender, and Mannequins in Museum Display,” Dress 45, no. 1 (2019): 81.

Stylization and Mimesis: Mannequin Design in the Interwar Years

For much of its history, Euro-American mannequin design can be plotted against a pendulum swinging between two representational poles: stylization and mimesis. By 1930, a “dialectic” developed between these distinct approaches. [10] Reviewing examples of these approaches will situate the mannequins designed for the 1937 Exposition. Furthermore, I will draw attention to how these examples correspond to theories of bodily “containment” put forth by art historian Lynda Nead in her influential feminist critique of the female nude. This European artistic tradition, Nead argues, seeks to contain and regulate the female body. She explains: “the forms, conventions, and poses of art have worked metaphorically to shore up the female body—to seal orifices and prevent marginal matters from transgressing the boundary dividing the inside of the body and the outside, the self from the space of the other.” [11] Nead acknowledges that containment is not exclusive to fine art production. Fashionable dress physically contains, conceals, and contorts the body, and therefore is ripe for the application of Nead’s argument. For the purposes of this article, I will extend ideas of containment to the mannequin. Despite their differing representational programs, stylization and mimesis will be shown to perpetuate a “magical regulation of the female body.” [12] In contrast, the mannequins deployed at the 1937 Exposition signal the opposite, which Nead describes as “the body without borders,” [13] and which I analyze within the context of the 1930s as a “fragmented body.”

The Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes opened in Paris in 1925 after initial plans for 1916, and later 1922, were delayed. Unlike previous French expositions universelles, such as those staged in 1878, 1889, and 1900, which represented the entire process of industrial manufacturing, the Exposition Internationale of 1925 celebrated the finished commercial product. Fashion figured prominently in this ode to commerce and the commodity. The Pavillon de l’Élégance was a particularly important venue for fashion at the Exposition, as it marked the first time that Parisian couture was exhibited in a standalone pavilion, rather than amongst other needle trades in a general textile building. In the bright and open interior of the Pavillon de l’Élégance, four giants of Parisian couture — Callot Sœurs, Jenny, Lanvin, and Worth—employed a time-tested technique of drawing on the language of high art to sustain the “aura” of French fashion, which had suffered amidst the devastating impacts of the war. [14]

[9] See Rachel Lee, “Why Representation Matters: Creating the Africa Fashion Mannequin,” January 25, 2023, https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/projects/why-representation-matters-creating-the-africa-fashion-mannequin.

[10] Sara K. Schneider, Vital Mummies, 129; see also Nicole Parrot, Mannequins (London: Academy Editions, 1982), 121.

[11] Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality (London; New York: Routledge, 1992), 6.

[12] Nead, The Female Nude, 7.

[13] Ibid., 2.

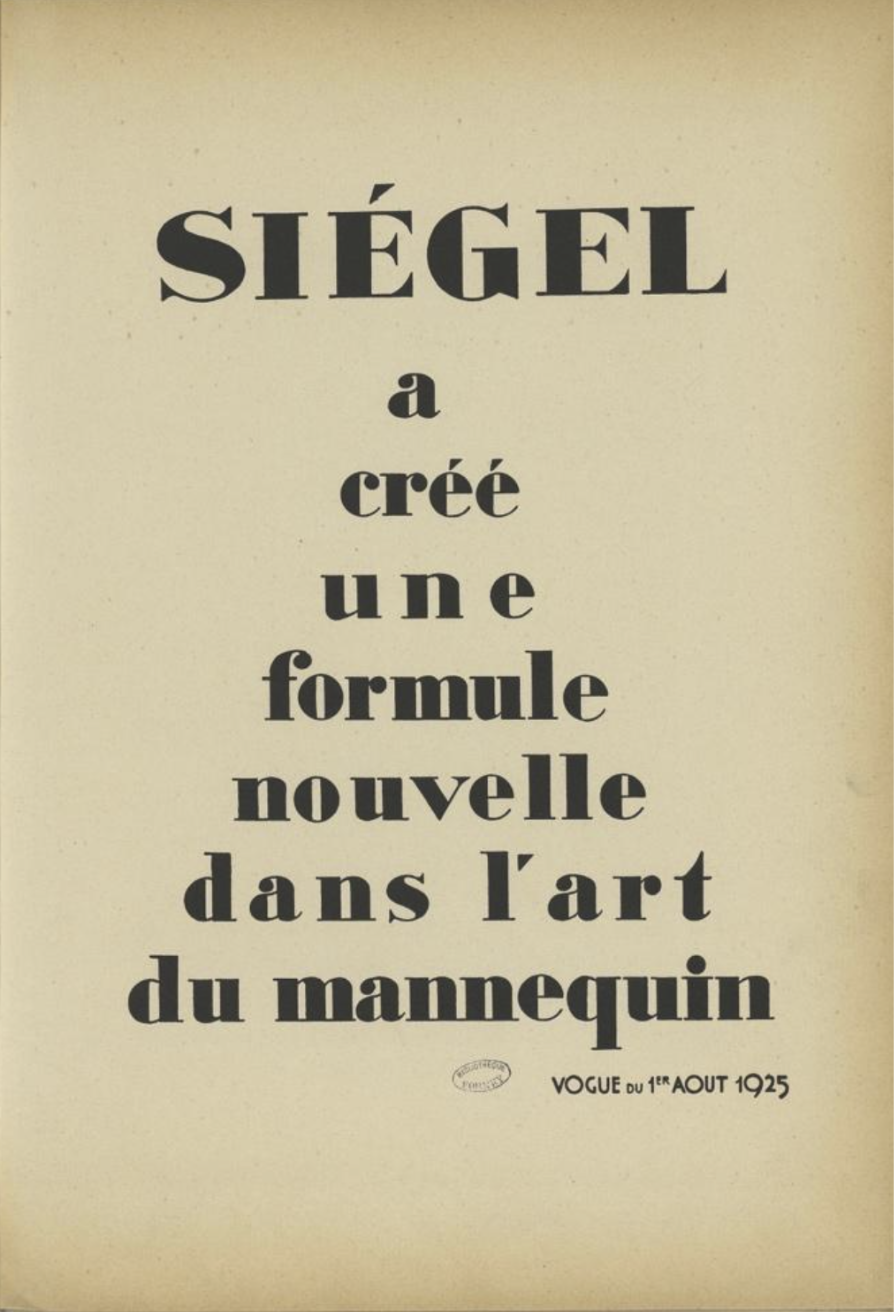

The significance of fashion at the Exposition was not merely due to its ubiquity. Organizers, participating designers, and the press were attentive to how fashion was displayed, including the mannequins designed by the manufacturer Siégel expressly for debut at the event. [15] Four months after the Exposition opened, Vogue triumphantly declared (Figure 2). that Siégel had “created a new formula in the art of the mannequin.” [16]

[14] Nancy Green, “Art and Industry: The Language of Modernization in the Production of Fashion,” French Historical Studies 18, no. 3 (1994): 722-48.

[15] In 1895, the Canadian businessman Victor-Napoléon Siégel began manufacturing various retail display props. An alliance with Stockman in 1924 led Siégel to expand into mannequin production.

[16] “Siégel à créé une nouvelle formule dans l’art du mannequin,” Vogue, 1 August, 1925, 41, Gallica—Bibliothèque Nationale de France. (All translations of French to English are my own. The original French text will be included in the footnote when translation has occurred.)

Figure 2

Photographs of Callot Sœurs designs on Siégel Mannequins at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, Paris, 1925, published in a Siégel Catalogue, 1926, 38 x 27 cm, Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

Figure 3

Photographs of Callot Sœurs designs on Siégel Mannequins at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, Paris, 1925, published in a Siégel Catalogue, 1926, 38 x 27 cm, Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

Heads were simplistic ovals with facial features reduced to contours. Wigs of human hair were replaced with geometric shapes and sculpted deco curls. The basis for the mannequins were fashion illustrations, rather than live models. [17] Delicate yet evocative gestures, such as the cock of a wrist or tilt of head, perform a gestural language of fashion that remains visible in shop windows and fashion photography to this day. The sinuous nonchalance of the mannequins harmonizes with the principles of modernist fashion of the period, which had largely abolished restrictive corsetry and cumbersome crinolines that inhibited movement.

Although Siégel’s serene mannequins might appear “liberated” from the rigidity of nineteenth-century fashion and its mimetic mannequins, aspects of their design perpetuate bodily containment. First, the smooth wax surface effectively seals the body and renders it impermeable. Second, the monochrome treatment of the body, especially facial features, utilized in certain designs corresponds to Nead’s definition by reducing the visual impact of orifices (Figure 3). This colouration is difficult to discern in black and white photographs. However, a Siégel catalogue from 1926 describes “painted and polychrome” figures in hues of gold, silver, gray, pale pink, red, dark amethyst, and “ebony.” [18] With faces rendered in a singular colour, the mannequins are rendered incapable of returning the gaze of the viewer, thereby performing femininity anchored in passivity.

Notwithstanding Vogue’s celebration of the mannequins, the overall press reaction was mixed. Many critics took issue with the painted surface colours. For example, one reviewer questioned whether the “epileptic” poses and silver, gold, and brown tints were “really the feminine ideal of the day?” She ultimately concluded that the mannequins were “ugly to the limit of ugliness.” [19] Despite its departure from mimesis, the stylized mannequin is still assessed in relation to an idealized fashionable feminine body, and therefore participates in the regulation of women’s bodies that is central to containment.

[17] Gayle Strege, “The Store Mannequin: An Evolving Ideal of Beauty,” in Visual Merchandising: The Image of Selling, ed. Louisa Iarocci (Farnham; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 103.

[18] Siégel Catalogue, 1926, Réserve VIO 32, Bibliothèque du Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

[19] Grèges, “A propos de l’exposition des arts décoratifs,” 26 [« des mannequins laids jusqu’à la limite de la laideur... Est-ce que ces femmes […] aux poses épileptiques, au teint argenté, doré, vert, or marron, sont vraiment l’idéal féminine de l’époque? »].

During the interwar period, mimesis is most associated with the work of American mannequin designers, including Cora Scovil and Lester Gaba, who famously modelled their forms off recognizable actors and socialites. [20] The extreme to which these designers pushed mimetic representation is understood as a reaction to the growing influence of surrealism in commercial display. [21] Rejecting this artistic stylization, Gaba sought to create mannequins with a “typical American look.” [22] He received commissions from department stores whose directors hoped the lifelike yet idealized figures would “provoke purchases through the consumers’ psychological attraction to a more perfect version of their own image.” [23]

In 1932, Gaba debuted a mannequin modelled after the socialite Cynthia Wells. Gaba’s “Cynthia” was anthropomorphized by her maker, becoming a celebrity in her own right. She was photographed dining at restaurants with Gaba and was featured in Life magazine. Technology historian Alana Staiti suggests that Cynthia, with her “artificially feminine demeanour” may have functioned as Gaba’s beard by providing “heteronormative cover.” [24] Staiti also highlights how anthropomorphic mannequins such as Cynthia become models of “attentiveness to one’s own-self fashioning.” [25]

Marketing mannequins as real women invites identification and dangerous comparison with an unrealistic body made to look lifelike through mimesis.

[20] Sara K. Schneider, “Body Design, Variable Realisms; The Case of Female Fashion Mannequins,” Design Issues 13, no. 3 (1997): 8.

[21] Schneider, “Body Design,” 8 and Staiti, “Real Women,” 417.

[22] Orr, “Body Doubles,” 50.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Staiti, “Real Women,” 421.

[25] Ibid., 423-4.

Nead’s theory of containment also considers the impacts of the representational tropes of the female nude. Woman is both “viewed object and viewing subject, forming and judging her images against cultural ideals and exercising a fearsome self-regulation.” [26] Mannequins like Cynthia correspond to Nead’s theory of containment by perpetuating two levels of self-regulation; first, in the anthropomorphized mannequins, and, second, in the viewing subjects that aspire to the highly constructed bodies naturalized through mimesis. Nead describes the effects of containment on subjectivity:

What seems to be at stake in all these discourses, and what all these areas have in common, is the production of a rational, coherent subject. In other words, the notion of unified form is integrally bound up with the perception of self, and the construction of individual identity. Psychoanalysis proposes a number of relations between physical structures and the perception and representation of the body. Here too, subjectivity is articulated in terms of spaces and boundaries, of a fixing of the limits of corporeality. [27]

By physically containing the body, the artistic construction of the female body implies a fixed and stable corporeal home for the self. Thus, the female nude — and by extension, the fashion mannequin — is entangled in a perceived relationship between body and self that locates identity within the wholeness of the body. By rejecting wholeness and containment, the mannequins designed by Couturier bring this entanglement to the fore.

Couturier’s Mannequins at the Exposition Internationale, 1937

As was the case in 1925, novel mannequins were specifically designed for debut at the Pavillon de l’Élégance during the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937). This version of the Pavillon was expanded to include twenty-nine couturiers. The organizers considered it to be a prototype for the exhibition of the future. According to their own report, they proudly abandoned the conventions rehearsed by previous expositions, which included ordinary stands, vitrines, shelves, and the mannequin du magasin. [28]

The Pavillon organizers regarded mannequins as pivotal to “renewing the art of presenting fashion” in this so-called exhibition of the future. [29] Despite this stated importance and their unconventional design, existing accounts of the mannequins are limited to a few pages or mere paragraphs. The literature has thus far avoided analysis and tends to repeat information, such as the following quote by Robert Couturier that is published in at least four texts:

I wanted tragic silhouettes that were intentionally devoid of any of the pleasantness, the gentleness, that usually go with elegance. Their defensive, frightened gestures, their featureless faces, their badly balanced bodies, recalled the inhabitants of Pompeii surprised by a cloud of ashes rather than the habitués of the Faubourg Saint-Honoré or avenue Montaigne. [30]

Couturier’s insight is important as a testimony to his dismissal of the standard fashionable elegance in favour of terror and torment. However, this curious statement begs for context, discussion, and analysis. As such, the following pages contribute a greater understanding of Couturier’s forms in their time and place, including the larger picture of mannequin design and the cultural context of the interwar period.

Couturier’s mannequins completely abandoned the “formula” established by Siégel in 1925 (even though Siégel also produced these mannequins). In terms of design, stylization was pushed into abstraction. Facial features were completely effaced. Surfaces were textured to appear rough and bumpy. Bodily proportions extended beyond anatomical possibility; torsos were spindly, waists were emaciated, and arms and hands were brawny and oversized. The mannequins stood at a towering seven feet tall. With such unusual dimensions, participating designers were required to produce custom garments for these ungainly “clients.”

[26] Nead, The Female Nude, 10.

[27] Ibid., 7.

[28] Jean Labusquière, “Introduction,” Le Pavillon de l’Élégance, 1938, B9.A1.E5.1480, Bureau International des Expositions, Paris [« Qu’on le veuille ou non, nous aurons rendu difficile, sinon vraiment insupportable, la répétition du stand ordinaire, de la vitrine aux tablettes de verre ou du mannequin du magasin. »].

[29] “Les Mannequins” in Le Pavillon de l’Élégance, 25

[« … le mannequin de Couturier a renouvelé l’art de présenter les modèles. »].

[30] Ghislaine Wood, The Surreal Body: Fetish and Fashion (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 23; Schneider, Vital Mummies, 129; Parrot, Mannequins, 147; and Orr, “Body Doubles,” 46.

An unsettling panic is discernible in Otto Wols’ photograph of Madeleine Vionnet’s display in the Pavillon de l’Élégance, where two mannequins forcefully throw their hands back towards their heads (Figure. 4). This is one of the estimated 4,000 negatives that Wols, a German painter and photographer, produced during the 1937 Exposition. These were printed as postcards to be sold outside the Pavillon de l’Élégance, preserved as fine art prints, and published in fashion magazines.

Magazine editors reportedly struggled to utilize Wols’ high-contrast images because they diverted attention away from the garments by focusing on the awkward bodily contortions of the mannequins. [31] The dramatic poses in the Vionnet display align more with the shock of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) than the demure elegance circulating in fashion magazines. The intensely arched back of the leftmost mannequin seemingly foreshadows an impending fall or loss of consciousness. Viewers are left uncertain as to whether the rightmost mannequin is rushing to her aid or if she is the source of her anguish. Based on existing images, Wols photographed this scene from at least four different perspectives. His studied photographic treatment heightens the overarching tension by placing the foreboding arch between the two mannequins. This mysterious void lingers as the source of fear and the unknown — is it concealing the reason for their screams?

[31] Nina Schleif, email message to author, September 25, 2019.

Figure 4

Postcard with photograph by Otto Wols depicting the Madeleine Vionnet display in the Pavillon de l’Élégance at the Exposition Internationale de Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris, 1937.

Postcard: author’s own

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All reproductions of the works are excluded from the CC: BY License

Figure 5

Postcard with photograph by Otto Wols depicting the Edward Molyneux display in the Pavillon de l’Élégance at the Exposition Internationale de Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris, 1937.

Postcard: author’s own

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All reproductions of the works are excluded from the CC: BY License

Wols’ photograph of the Vionnet display accurately portrays an important interaction between mannequins and the spatial infrastructure of the Pavillon de l’Élégance. Couturier worked closely with the architects of the Pavillon de l’Élégance to create a Gesamtkunstwerk-like environment. [32] Low ceilings, tight crevices, and winding corridors inspired comparisons to a grotto, cave, or labyrinth. These eerie locales provide a perfect setting for the frightened and tormented mannequins. Moreover, the mannequins, the interior walls of the Pavillon, and the scenographic props were all cast in a pale pink plaster indented to convey the appearance of terracotta. Couturier was enticed by plaster; it was the sculptor’s preparatory material. [33] In his words, the material was “so criticized and despised for its unpleasant aspect, [it was] almost worthless.” [34] Intentionally using a “worthless” and “despised” material further distances Couturier’s design from the idealized and aspirational mannequins of the interwar period.

The harmony between the mannequins and their surroundings in the Pavillon de l’Élégance is apparent in Wols’ photograph of Edward Molyneux’s display (Figure 5). In this scene, the mannequin is positioned beside a column and facing away from the viewer. The cut of the dress reveals the mannequin’s bare back and outstretched arm. The lighting — perhaps dramatized by Wols — emphasizes the rough, uneven surface of both the mannequin and the column. Furthermore, this intense lighting casts a shadow of the mannequin on the opposite wall. In the dark, flat shadow, the curves of the mannequin’s waist and hips echo those of the adjacent column. Just as the column is an architectural support, the mannequin is an indispensable support for fashion display.

[32] Lucy McKenzie and Beca Lipscombe, eds., Atelier E.B. Passer-by (Paris: Lafayette Anticipations; London: Koenig Books, 2019), np.

[33] Ghislaine Wood, The Surreal Body: Fetish and Fashion (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 21.

[34] Robert Couturier quoted in Wood, The Surreal Body, 21.

In her account of bodily fragmentation in modern art, art historian Linda Nochlin puts forth a provocative thought: Gesamtkunstwerk is a strategy for overcoming fragmentation. Modernity, she suggests, is equally “marked by the will toward totalization as much as it is metaphorized by the fragment.” [35] The Gesamtkunstwerk fostered by the mannequins and their spatial environment in the Pavillon de l’Élégance ends at the garments. The contrast between the smooth surfaces and precise finishings of the garments and the rough surface of the mannequin is startling. Returning to the Wols’ photograph of the Vionnet display, this discord is illustrated in the rightmost mannequin. The folds of neoclassical drapery that cascade the length of the mannequin are emphasized by dramatic lighting, making it seem as though they were sculpted in marble. By working on the bias, Vionnet accentuates the three dimensionality and wholeness of the body. [36] As it clings to the contours of the mannequin, the dress reveals a bend in the left leg. This contrapposto stance is a trope of classical sculpture that Nead identifies as key to “the act of artistic regulation” inherent to containment. [37] However, the position of the mannequin’s arms deny the ideal bodily balance sought by contrapposto. By drawing attention to the physicality of the mannequin, Vionnet’s draped gown invites comparisons between the perceived stability of classicism and the instability of Couturier’s mannequins.

[35] Linda Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 53.

[36] Rebecca Arnold, “Vionnet…Classicism,” in Classic and Modern Writings on Fashion, ed. Peter McNeil (London: Berg, 2009), DOI: 10.5040/9781847887153.v4-0113.

[37] Nead, The Female Nude, 20.

[38] Helen Roche, “Mussolini’s ‘Third Rome,’ Hitler’s Third Reich and the Allure of Antiquity: Classicizing Chronopolitics as a Remedy for Unstable National Identity?”, Fascism 8, 2 (2019): 127-8.

[39] Anson G. Rabinbach, “The Aesthetics of Production in the Third Reich,” Journal of Contemporary History 11, no. 4 (1976): 43.

Figure 6

Statue by Josef Thorak in front of the German Pavilion, designed by Albert Speer, at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris, 1937. Photograph by Willem van de Poll, Nationaal Archief, The Hague Rights: Public Domain, https://picryl.com/media/voorzijde-van-het-duitse-paviljoen-met-een-beeldengroep-van-josef-thorak-bestanddeelnr-c0cac9.

The Exposition Internationale of 1937 occurred at a time when classicism was being “appropriated” and “abused” by developing fascist movements in Europe, namely Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany. [38] Historians identify this effort to “legitimize political rule through aesthetic symbolization” as a factor that distinguishes twentieth-century fascism from other authoritarian regimes. [39] Depictions of an ideal body that embodied Nazi eugenics and ideologies of racial supremacy were pivotal to the propagandistic program of the Third Reich. [40] The idealized body politic was given material form through monumental public sculptures that were “uncompromisingly whole,” [41] such as those commissioned for the Berlin Olympics in 1936 and the pair of three nudes flanking the entrance of the German pavilion at the Exposition Internationale (Figure 6). The soaring neoclassical façade of the German pavilion faced the equally imposing Soviet pavilion, thus dwarfing the surrounding buildings and marking a cultural standoff that would soon manifest militarily. [42] In light of the considerable scholarship that has identified prewar tensions in these pavilions, it is nearly impossible to overlook the tormented and frightened mannequins in the Pavillon de l’Élégance as a sinister premonition of the horrors that would soon play out in Europe.

Expressions of Fragmentation

Visual culture of the interwar period includes contradictory visions of the modern body. Despite their differing approaches, both wholeness and fragmentation are considered responses to the devastation and traumas of the First World War. On the one hand, desires to put the individual and collective body back together resulted in “images of wholeness” in French, British, and American governmental imagery. [43] Aesthetics of wholeness, stability, and containment were made fashionable by designers including Madeleine Vionnet, Madame Grès, and Mario Fortuny, and, as noted above, were exploited by fascist regimes.

On the other hand, expressions of a decidedly broken, fragmented, and uncontained body proliferated in visual culture. Experiments with bodily fragmentation have been linked to the prevalence of amputation after the war. [44] Additionally, experiences of “shell shock” and electro-shock therapy — the most common treatment for this post-traumatic condition — have been connected to the works of montage created by Dada artists in the 1920s. [45] Acts of slicing, splicing, and reconfiguring in montage entail a certain violence when applied to representations of the body, as exemplified in Hannah Hoch’s well-known reflection on the commodification of women’s bodies in The Beautiful Girl (1920). Surrealism also “reveled in representations of bodily fragmentation and dismemberment.” Art historian Amy Lyford explains how early “‘surreality’ would be used like a knife to separate hand from arm.” [47] Dada and surrealist practices of fragmentation destabilize perceptions of the body as whole and stable. Bodily experiences of wartime conflict and subsequent artistic expressions thereof have been predominantly associated with men, however, women’s bodies were “a crucial battleground” for the tensions between “classicism and wholeness versus Surrealism and fragmentation.” [48]

[40] Jeffery Richards, “Mangan and Masculinity: Leni Riefenstahl, Charlie Chan, Tarzan and the 1936 Olympics,” in Manufacturing Masculinity; The Mangan Oeuvre: Global Reflections on J.A. Mangan’s Studies of Masculinity, Imperialism, and Militarism, ed. Peter Horton (Berlin: Logos Verlag, 2017), 30.

[41] Lucy Moyse Ferreira, “Fragmentation,” in Danger in the Path of Chic: Violence in Fashion Between the Wars (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), DOI: 10.5040/9781350126312.ch-2.

[42] Yve-Alain Bois et al., “1937a” in Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, vol. 1, 1900-1944 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2011), 307. For prewar tensions at the 1937 Exposition, see also Danilo Udovički-Selb, “Facing Hitler's Pavilion: The Uses of Modernity in the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition,” Journal of Contemporary History 47, no. 1 (2012): 13-47; Karen Fiss, Grand Illusion: The Third Reich, the Paris Exposition, and the Seduction of France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Dawn Ades et al., Art and Power: Europe Under the Dictators 1930-45 (London: Hayward Gallery, 1995).

[44] Ferreira, “Fragmentation.”

[45] See Brigid Doherty, “‘See: ‘We Are All Neurasthenics!’ or, The Trauma of Dada Montage,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (1997): 82-132.

[46] Amy Lyford, “The Aesthetics of Dismemberment: Surrealism and the Musée du Val-de-Grâce in 1917,” Cultural Critique 46 (2000): 46.

[47] Lyford, “The Aesthetics of Dismemberment,” 53.

[48] Ferreira, “Fragmentation.”

In 1936, Jacques Lacan introduced his psychoanalytic theory of bodily wholeness and fragmentation as it relates to subjectivity. The mirror stage occurs in infants between the ages of six and eighteen months. The infant’s recognition of themselves in the mirror as a distinct subject, separate from others and their surroundings, indicates their potential for corporeal wholeness. The visual Gestalt, or complete “bodily I” reflected in the mirror, is forever haunted by the fragmented body [le corps morcelé]. Memories of the alienated and uncoordinated body fuel the desire for a unified corporeal self. [49] Despite being a largely psychological process, the endless quest for wholeness experienced after the mirror stage “takes place on the surface of the body.” [50]

Lacan used metaphors and references to images to explain the fragmented body as “the form of disconnected limbs.” [51] He visualized the idea of a body coming undone through comparisons to paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and the “heterogeneous mannequin, a baroque doll, a trophy of limbs.” [52] While Lacan himself did not make this connection, his exploration of the “body in bits and pieces” has also been attributed to German artist Hans Bellmer’s work La Poupée. [53] This disturbing series involves photographs of mannequin and doll parts that appear violently disassembled and reassembled in a process akin to three-dimensional montage. Bellmer’s first Poupée dates to 1933, the year that Hitler was elected to power. The series is widely understood by art historians as a rejection of Nazism and its ideal body. [54] Indeed, Bellmer’s horrifying fragmentation rejects the wholeness of the body. Art historian Rosalind Krauss describes the Poupée series as “the endless acting out of the process of construction and dismemberment, or perhaps, the more exact characterization would be construction as dismemberment.” [55] Thus, the assemblage of dismembered doll parts hints to an alternative view of subjectivity in which deconstruction plays a pivotal role. However, considering that Bellmer did not begin with a complete doll but rather “worked continually from fragments,” this process can equally be described according to “the Lacanian realization that subjecthood is a series of components.” [56]

[49] Malcolm Bowie, Lacan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 26.

[50] Alison Bancroft, Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self (London: IB Tauris, 2012), 25.

[51] Jacques Lacan, Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: Norton, 2006), 78.

[52] Jacques Lacan cited in Bowie, Lacan, 26-27.

[53] Bowie, Lacan, 215.

[54] Adam Geczy, The Artificial Body in Fashion and Art: Marionettes, Models and Mannequins, (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 72.

[55] Rosalind Krauss, “Corpus Delicti,” October no. 33 (1985): 62.

[56] Geczy, The Artificial Body in Fashion and Art, 74.

Given Lacan’s interest in the continuous negotiation between the body and the self, his work can be extended to considerations of fashion. Fashion, as Alison Bancroft eloquently argues, “can be seen as one of the inevitable strategies employed to reconfigure the alienation at the center of the self.” [57] Indeed, fashion has been theorized as an embodied practice of subject formation involving processes of being and becoming. [58] By purporting to construct the self through clothing and modifying the body, fashion seeks to remedy experiences of fragmentation. This belief has been upheld by fashion media, which seemingly promotes “the same image-based ideal as the Lacanian whole body…[by] working towards the creation of an ideal if only in the realm of images. [59] However, Bancroft and Lucy Moyse Ferreira have shown that fashion media occasionally rejects the ideal of the unified body by evoking psychoanalytic fragmentation. [60] A similar pattern is discernable in mannequins. Although the mannequin typically exemplifies containment, wholeness, and a mythical union of body/self, Couturier’s mannequins were not immune to the widespread cultural anxieties surrounding bodily fragmentation.

[57] Bancroft, Fashion and Psychoanalysis, 25.

[58] See, for example, Entwistle, The Fashioned Body, 30-39, and Susan B. Kaiser and Denise N. Green, Fashion and Cultural Studies, 2nd ed. (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), 26-29.

[59] Ferreira, “Fragmentation,” DOI: 10.5040/9781350126312.ch-2.

[60] See Bancroft’s discussion of Nick Night’s photography in Fashion and Psychoanalysis: and Ferreira’s analysis of interwar fashion media in the chapter “Fragmentation” in Danger in the Path of Chic.

The Fragmented Fashion Body

Returning to the Pavillon de l’Élégance, it is evident that Couturier’s mannequins participate in a broader visual and conceptual program of fragmentation.

The fragility of plaster implies a fragility of the body; the mannequins appear as if they might crack and crumble into dusty rubble at any moment. As a preparatory material, plaster has immortalized the mannequins as permanently unfinished. They are suspended between construction and deconstruction in a state akin to Lacan’s description of the subject-in-process as a Janus-faced structure that looks forward (to the ego) and backward (to the fragmented body). [61] Adorned in luxuriously finished garments, Couturier’s mannequins, in their eternal fragmentation, skew the role of the mannequin a proxy for the construction of the self. By rejecting the premise of bodily wholeness and unity that fuels the modern fashion system, Couturier’s mannequins act, rather, as agents of instability.

Themes of instability and deconstruction are foregrounded in Elsa Schiaparelli’s display in the Pavillon de l’Élégance. At first glance, Schiaparelli and Couturier’s approaches to design seem to resonate on multiple levels. For instance, Couturier’s embrace of plaster as a “worthless” material aligns with Schiaparelli’s use of unconventional materials and finishings. In this regard, both defy expectations of the finished and fashionable object. Furthermore, from a Lacanian perspective, Schiaparelli’s designs can also be understood to destabilize subjectivity. Caroline Evans explains:

If fashion is the glue that binds identity, in Schiaparelli’s hands it becomes a solvent: through trickery, allusion and wit different layers of meaning are elaborated in a series of designs that, far from constructing identity as fixed, actually deconstructs it as a “becoming.” In the process it destabilizes notions of the sovereign self, or the “subject,” in favor of the shifting and uncertain meanings of a subject in process. [62]

[61] Bowie, Lacan, 26, 182.

[62] Caroline Evans, “Masks, Mirrors, and Mannequins: Elsa Schiaparelli and the Decentered Subject,” Fashion Theory 3, no. 1 (1999): 8.

Lacanian fragmentation reverberates in this description of the instability of the self and the subject in process. Both Schiaparelli and Couturier reverse the conventional premise of fashion to affirm the subject in body and mind.

Considering the material and conceptual affinities between Schiaparelli and Couturier, the extent to which Schiaparelli disliked the mannequins in the Pavillon de l’Élégance is surprising. She reportedly criticized the figures as “grotesque and not at all in keeping with the spirit of smart dressing.” [63] She refused to dress the mannequin that was allocated to her. As a result, the mannequin reclining on a bed of flowers in front of the Schiaparelli signage is entirely unclothed. “Naked as the factory had delivered it” recalled Schiaparelli in her autobiography. [64] Ironically, by virtue of being unclothed, Schiaparelli’s mannequin draws more attention to its bodily state. The mannequin holds a pair of gloves in one hand while a floral evening dress and high-heeled shoes — perhaps intended as a getaway outfit — are carefully positioned nearby. The scene, as photographed by Wols, was largely considered too provocative to appear in any of the major French fashion journals. [65] Visitors interpreted the undressed mannequin as a corpse; one guest even left behind a condolence card. [66]

For her display in the Pavillon de l’Élégance, Schiaparelli had intended to use “Pascal,” the articulated male mannequin displayed in the window of her boutique at the Place Vendôme. With a smooth wooden surface and delicate neoclassical features, the mannequin adheres to aesthetics of containment and wholeness. Schiaparelli lovingly animated Pascal in a way that “destabiliz[es] the boundaries of identity, between human and dummy, animate and inanimate.” [67] This treatment reveals the mannequin as the embodiment of the “marvellous,” or the blurring of animate and inanimate strongly associated with surrealism. Art historian Hal Foster explains that the mannequin intrigued the surrealists because it symbolized the uncanny reversals playing out on bodies and objects in the high capitalist era. [68] It is important to note that notorious surrealist interventions with mannequins, namely Bellmer’s Poupée series, Salvador Dalí’s shop window designs for Bonwit Teller (1936; 1939), and “Mannequin Street” at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme (1938), involved mimetic mannequins. The lifelike surrogate body was necessary to activating the “marvellous” because it functioned as “the foil for the artists to transgress or mutilate in an attempt to create a frisson for the spectator.” [69] Couturier’s withered and fragmented figures were already too far from the anatomical human form to generate this uncanny effect.

Although Couturier’s mannequins were too fragmented to activate the “marvellous,” they were not entirely immune from additional visual fragmentation. In addition to photographing the completed Pavillon de l’Élégance, Wols recorded many images of the site during its construction. Numerous photographs from this phase depict Couturier’s mannequins unclothed and in various states of bodily (in)completeness. One closely cropped image documents a pile of various mannequin parts (Figure 7). This eerie image of spare parts perfectly visualizes the Lacanian fragmented body by confusing bodily assembly and disassembly. A photograph portraying individual mannequin hands emerging from a wooden crate filled with straw captures the rigidity and tension of Couturier’s roughly modelled mannequins (Figure 8). Rejecting the delicate fashion gestures of the 1925 “formula,” widely splayed fingers reach out from the crate as if grasping for life while the body drowns beneath the surface. The outstretched hands might simply be awaiting construction during the installation the Pavillon de l’Élégance, or they might signify the final sign of life from a body already in the process of deconstruction.

[63] Letter from Marcia Connor to Grover Whalen, Subject: Schiaparelli’s Suggestion, December, 4, 1937, New York Public Library Research Libraries, New York World’s Fair 1939/40, Box 444.

[64] Elsa Schiaparelli, Shocking Life: The Autobiography of Elsa Schiaparelli (London: V&A Publications, [1954] 2007), 74.

[65] Victoria R. Pass, “Schiaparelli’s Dark Circus,” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 1, no 1 (2014): 36.

[66] Richard Martin, Fashion and Surrealism (New York: Rizzoli, 1988), 56.

[67] Evans, “Masks, Mirrors, and Mannequins,” 22.

[68] Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 126.

[69] Kachur, Displaying the Marvelous, 42.

Figure 7

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Wols, Georg Heusch, Teile von Dekorationspuppen, Negative 1937; Print 1976, Gelatin Silver Print, Image: 15.9 × 15.3 cm (6 1/4 × 6 in.); Sheet: 17.7 × 23.9 cm (6 15/16 × 9 7/16 in.)

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All reproductions of the works are excluded from the CC: BY License

Detached mannequin hands reaching out of a straw-filled box.

Figure 8

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Wols, Georg Heusch, Pavillon l’Élégance Hands, Negative 1937; Print 1976, Gelatin Silver Print

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All reproductions of the works are excluded from the CC: BY License

Commercializing the Fragmented Fashion Body

Critical and commercial responses to Couturier’s mannequins introduce a final consideration that further illuminates the tensions between wholeness and fragmentation characteristic of the interwar period. Nicole Parrot summarizes public opinion of the mannequins as follows: “Some critics spoke of a gallery of monsters, but the majority were enthusiastic.” [70] Press extracts published in the catalogue of the Pavillon de l’Élégance describe the faceless mannequins as conveying the visitor’s dreams. [71] By eliminating facial features, Couturier’s abstraction of the body seemingly liberates identification on the part of the viewer. The feelings of “magic,” “mystery,” and “fantasy” described in the press are antithetical to the logic behind Gaba’s idealized mimetic mannequins — that their perfection would fuel consumer desire. Despite the stated intention to do away with the conventional mannequin du magasin, Couturier’s forms were promptly ordered by department stores in Paris, London, Chicago, New York, and Tokyo. [72]

Couturier’s mannequins were adapted and subdued by Siégel for the commercial market. A four-page spread in the April 1939 issue of Marie Claire documents the manufacturing process of these mannequins at the Siégel atelier (Figure 9 and 10). The design, casting, assembling, plaster coating, packing, and shipping of the mannequins are captured in captioned photographs arranged sequentially like a comic strip. Of the eighteen photographs in the Marie Claire spread, only two include a complete mannequin. With a focus on the manufacturing process, most of the images depict mannequins missing limbs or heads. There is as palpable tension between the photographs of these incomplete mannequins and the captions that animate them with qualities of a “real woman” [une vraie femme]. The narrative of a male artisan making the mannequin whole, and thus a “real” woman, is emphasized in the image of an artisan attaching an arm to a headless mannequin. Positioned at the shoulder and wrist, the artisan’s hands seemingly give life to the outstretched mannequin hand centered in the composition. The accompanying caption explains the story of a “woman cut into pieces” [la femme coupée en morceaux] who comes to life like Galatea, the statue made by the mythological sculptor Pygmalion who falls in love with his creation. In the next scene, the mannequin is described as a “newborn woman finally alive” [la femme nouvelle-née, enfin « vivante »]. Through a combination of text and image, the Marie Claire spread reveals a desire to restore the fragmented body to wholeness.

[70] Parrot, Mannequins, 148.

[71] Martine Rénier, extract from Femina, « … parce que le sculpteur a voulu que nous plaçons sur chacune d’elles le visage de nos songes » ; Raymond Isay, extract from La Revue des Deux Mondes, « celles-là incarnent le rêve… » ; extract from Être Belle, « sans une trop grande précision de traits afin de laisser à l’imagination de chacun le pouvoir magique de recréer et de transformer les modèles présentés » in Le Pavillon de l’Élégance, 13-14.

[72] McKenzie and Lipscombe, eds., Atelier E.B. Passer-by, np and Orr, “Body Doubles,” 46.

Figure 9 & 10

“Vendeuses de Cire,” Marie Claire, April 1938, 14-17. Gallica – Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

There are no equivalent images amongst the ample visual documentation of Couturier’s original mannequins; the fragmented bodies exist outside the comparative context of the live human body. The final Marie Claire frame presents a standoff between two types of bodies: the fragmented surrogate and the live body in its completed splendour. Outside of the eerie environment of the Pavillon de l’Élégance, Couturier’s design was out of place and unsuccessful. Reportedly, “window dressers found them inconvenient and women refused to identify with them.” [73] In light of this rejection, it is impossible to avoid foreshadowing the horrors that would transpire mere months after the Marie Claire feature was published. On the eve of Second World War, perhaps the violence and trauma embodied in the fragmented body registered on a deeper level for viewers.

[70] Parrot, Mannequins, 150.

Conclusion

The mannequins designed by Robert Couturier for the Pavillon de l’Élégance reject the idealization, wholeness, and containment integral to the conventional fashion mannequin. Instead, Couturier’s abstract plaster forms fossilize the surrogate fashion body in a permanent state of incompleteness. With an emphasis on bodily fragility, the mannequins participate in a broader cultural program of fragmentation that includes various artistic expressions and the psychoanalytic theory put forth by Jacques Lacan. Couturier’s mannequins materialize Lacan’s image of the fragmented body and associated model of subjectivity that blurs construction and deconstruction. Thus, Couturier’s mannequins offer an alternative view of the surrogate fashion body in processes of identification and subjectivity. Although Couturier’s design departs from convention, it underscores the importance of mannequins to the creation and communication of meaning. Ultimately, the fragmented, withered, and tense mannequins reflect their unique historical and cultural context, when the traumas of wartime overlapped with a foreboding premonition of the horrors to come.

Works Cited

Arnold, Rebecca. “Vionnet…Classicism.” In Classic and Modern Writings on Fashion, edited by Peter McNeil. London: Berg, 2009. DOI: 10.5040/9781847887153.v4-0113.

Bancroft, Alison. Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self. London: IB Tauris, 2012.

Bowie, Malcolm. Lacan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Chapin, Chloe, Denise Green, and Samuel Neuberg, “Exhibiting Gender: Exploring the Dynamic Relationship between Fashion, Gender, and Mannequins in Museum Display.” Dress 45, no. 1 (2019): 75-88.

Entwistle, Joanne. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory. Second Edition. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015.

Evans, Caroline. “Masks, Mirrors, and Mannequins: Elsa Schiaparelli and the Decentered Subject.” Fashion Theory 3, no. 1 (1999): 3-31.

Doherty, Brigid. “‘See: ‘We Are All Neurasthenics!’ or, The Trauma of Dada Montage.” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (1997): 82-132.

Ferreira, Lucy Moyse. Danger in the Path of Chic: Violence in Fashion Between the Wars. London: Bloomsbury. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350126312.

Fiss, Karen. Grand Illusion: The Third Reich, the Paris Exposition, and the Seduction of France. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Foster, Hal. Compulsive Beauty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Geczy, Adam. The Artificial Body in Fashion and Art: Marionettes, Models and Mannequins. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Green, Nancy. “Art and Industry: The Language of Modernization in the Production of Fashion.” French Historical Studies 18, no. 3 (1994): 722-48.

Grèges, Fany. “A propos de l’exposition des arts décoratifs: opinion des femmes.” Les Modes: Revue mensuelle illustrée des arts décoratifs appliqués à la femme, July 1925. Gallica– Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Herbert, James D. “The View of the Trocadéro: The Real Subject of the Exposition Internationale, Paris, 1937.” Assemblage 26 (1995): 94-112.

Iarocci, Louisa, ed. Visual Merchandising: The Image of Selling. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013.

Kachur, Lewis. Displaying the Marvelous: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Surrealist Exhibition Installations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Kaiser, Susan B. and Denise N. Green. Fashion and Cultural Studies. Second edition, London: Bloomsbury, 2021.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Corpus Delicti.” October no. 33 (1985): 31-72.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: Norton, 2006.

Lee, Rachel. “Why Representation Matters: Creating the Africa Fashion Mannequin.” January 25, 2023. https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/projects/why-representation-matters-creating-the-africa-fashion-mannequin.

Le Pavillon de l’Élégance à l’Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques, Paris 1937. Paris: Les Soins d’Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1938. B9.A1.E5.1480. Bureau International des Expositions, Paris.

Lyford, Amy. “The Aesthetics of Dismemberment: Surrealism and the Musée du Val-de-Grâce in 1917.” Cultural Critique 46 (2000): 45-79.

Martin, Richard. Fashion and Surrealism. New York: Random House, 1987.

Matthews, Dyese L. and Kelly L. Reddy-Best, “Curating a Fashion Exhibition Centred on Black Women: Combatting Individual and Systemic Oppressions at Land-Grant University Fashion Museums.” Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 13 (2022): 141-166.

Matthews David, Alison. “Body Doubles: The Origins of the Fashion Mannequin.” Fashion Studies 1, no. 1 (2018): 1-46. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010107.

McKenzie, Lucy and Beca Lipscombe, eds. Atelier E.B. Passer-by. Paris: Lafayette Anticipations; London: Koenig Books, 2019.

Mida, Ingrid. “Animating the Body in Museum Exhibitions of Fashion and Dress.” Dress 41, no. 1 (2015): 37-51.

Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality (London, New York: Routledge, 1992).

Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Harmonsworth: Penguin, 1971.

–––. The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

New York World’s Fair 1939/40 [Boxes 183, 444, 984, 1474, 1469]. New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York.

Orr, Emily. “Body Doubles: A History of the Mannequin.” In Ralph Pucci: The Art of the Mannequin, 35-55. New York: Museum of Arts and Design, 2015.

Parrot, Nicole. Mannequins. London: Academy Editions, 1982.

Pass, Victoria R. “Schiaparelli’s Dark Circus.” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 1, no. 1 (2014): 29-43.

Petrov, Julia. Fashion, History, Museums: Inventing the Display of Dress. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Rabinbach, Anson G. “The Aesthetics of Production in the Third Reich.” Journal of Contemporary History 11, no. 4 (1976): 43–74.

Richards, Jeffery. “Mangan and Masculinity: Leni Riefenstahl, Charlie Chan, Tarzan and the 1936 Olympics.” In Manufacturing Masculinity; The Mangan Oeuvre: Global Reflections on J.A. Mangan’s Studies of Masculinity, Imperialism, and Militarism, edited by Peter Horton, 29-42. Berlin: Logos Verlag, 2017).

Roche, Helen. "Mussolini’s ‘Third Rome,’ Hitler’s Third Reich and the Allure of Antiquity: Classicizing Chronopolitics as a Remedy for Unstable National Identity?", Fascism 8, 2 (2019): 127-152.

Schiaparelli, Elsa. Shocking Life: The Autobiography of Elsa Schiaparelli. London: V&A Publications, [1954] 2007.

Schneider, Sara K. Vital Mummies: Performance Design for the Show-Window Mannequin. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

–––. “Body Design, Variable Realisms; The Case of Female Fashion Mannequins.” Design Issues 13, no. 3 (1997): 5-18.

“Siégel a créé une nouvelle formule dans l’art du mannequin.” Vogue, August 1, 1925. Gallica-Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Staiti, Alana. “Real Women, Normal Curves, and the Making of the American Fashion Mannequin, 1932–1946.” Configurations 28, no. 4 (2020): 403-431.

Strege, Gayle. “The Store Mannequin: An Evolving Ideal of Beauty,” in Visual Merchandising: The Image of Selling, edited by Louisa Iarocci, 137-56. Farnham; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013.

Taylor, Lou. The Study of Dress History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Udovički-Selb, Danilo. “Facing Hitler's Pavilion: The Uses of Modernity in the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition.” Journal of Contemporary History 47, no. 1 (2012): 13-47.

Wilson, Elizabeth. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. London: Virago, 1985.

Wood, Ghislaine. The Surreal Body: Fetish and Fashion. London: V&A Publications, 2007.Works Cited

Author Bio

Paula Alaszkiewicz (she/her) is an Assistant Professor of Design and Merchandising and Curator of the Avenir Museum of Design and Merchandising at Colorado State University where she teaches textile and fashion history and museum practice. She holds a PhD in Art History from Concordia University in Montreal and an MA in History and Culture of Fashion from London College of Fashion. Paula’s research investigates the underlying structures and overlooked histories of fashion display that inform later practices of exhibiting and curating fashion. She engages with questions of theory, historiography, and temporality. Paula has worked closely with Judith Clark Studio and has consulted on exhibitions for fashion houses and museums.

Article Citation

Alaszkiewicz, Paula. “The Fragmented Fashion Body: Mannequins and the Paris Exposition Internationale, 1937.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-28, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050111.

Copyright © 2024 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)