Something Boro’d, Something Blue: An Analysis of Japanese Repair Practices and Material Scarcity

By Eric Larsen

DOI: 10.38055/FST030102

MLA: Larsen, Eric. “Something Boro’d, Something Blue: An Analysis of Japanese Repair Practices and Material Scarcity.” Fashioning Sustainment, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.38055/FST030102.

APA: Larsen, E. (2024). Something Boro’d, Something Blue: An Analysis of Japanese Repair Practices and Material Scarcity. Fashioning Sustainment, special issue of Fashion Studies, 3(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.38055/FST030102

Chicago: Larsen, Eric. “Something Boro’d, Something Blue: An Analysis of Japanese Repair Practices and Material Scarcity.” Fashioning Sustainment, special issue of Fashion Studies 3, no. 1 (2024): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.38055/FST030102.

Special Issue Volume 3, Issue 1, Article 2

Keywords

Resource scarcity

Boro

Japanese textiles

Patchwork

Abstract

Boro, a Japanese textile tradition rooted in resource scarcity, has evolved from a practice of necessity to an art form celebrated globally. At its core, boro involves utilizing scraps and off-cuts for garment creation and repair, often resulting in multi-generational textiles characterized by layers of patches. While modern interpretations often focus on sustainability and craftsmanship, this reduction overlooks the socio-economic conditions that shaped boro in Japan’s lower classes. Rectangular patchwork, indigo dye, and bast fibers became staples not by choice, but by necessity in a labour-rich, resource-poor economy. Though its origins lie in the shared struggles of those at the margins of society, today boro is a symbol of resilience and creativity. Boro has been revived as collectible artifacts and embraced as part of a philosophy which values the repurposing of goods. Whether reused in contemporary contexts like fashion or preserved as relics, boro’s dynamic essence defies being confined to static forms. Its fullest expression lies in its continued use, honouring the layers of history embedded within each piece.

“When people refer to the ‘good old days,’ they are most likely reminiscing about the past with a warm sense of nostalgia. But I ask: Were those good old days really so good? To me, the phrase simply betrays a rather naïve notion of history as a gentle current of time with historical incidents floating along the surface, while we reminisce about them fondly, without even being aware of those who were barely getting by at the bottom.”

-Tatsuichi Horikiri (The Stories Clothes Tell)

A History of Boro

Boro (ぼろ) refers to a class of historical Japanese textiles that have been patched, repaired, reinforced, or pieced together, often by hand, and at its most succinct can be described as “peasant cloth” (Fig. 1). The briefest accurate description would be that boro are pre-twentieth-century textiles, often but not always made of cotton, often but not always indigo-dyed, containing or composed of rectangular patches, and made by Japan’s lower classes, especially in colder and more isolated regions (Li 54).

Japanese textile artist Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada describes boro as “the state of objects that have been used, broken, or worn to tatters, then extensively repaired and sometimes used far beyond their normal expected life cycle” (Wada 278). Patchwork repair is certainly not limited to Japan, but what is often easiest to identify in boro is the generally substantial nature of the patchwork and the unified appearance many achieve, despite coming from disparate areas of Japan. The historical circumstances that lead to these shared characteristics of boro can be seen through Japan’s history with cotton, indigo, and local trade.

A central visual element of boro that Wada makes note of is that all the patches are rectangular:

A few important underlying aesthetics that unite all boro textiles…can be attributed to the fact that most Japanese traditional textiles are woven in units of 1 tan, which measures about 14 inches by 13 yards (roughly 35.5 cm by 12 m). Each tan, or bolt, is cut into a series of rectangular panels, which are then sewn together to create an article of clothing or utilitarian object. There is no cutting into the cloth for sleeves or darts like in Western clothing, which means that worn clothing could be easily taken apart and transformed into coverlets and mattresses (279-280).

The rectangular patches that define boro come from Japan’s traditional pattern drafting practices, a tradition which also yielded mostly rectangular off-cuts. Indeed, there is an asymmetry to many boro pieces which combine inconsistent human wear patterns with simple geometric patterns and shapes.

Prior to the introduction of cotton in Japan, fibres available to the lower classes were primarily bast fibres such as hemp or ramie. While cotton was introduced to Japan as early as the fourteenth century from China, cotton cultivation in Japan would not be firmly established until the eighteenth century—and even then, it was limited to warmer regions, with local trade restricted by the technology of the time (Wada 280). Bast fibres, while durable, were less comfortable and insulating than cotton, making cotton, even used rags, a scarce and valuable resource for families in colder conditions. As a result, a cotton rag trade developed within existing trade routes, such as those for fish and rice, and the opening of the Tohoku Main Line railway in 1892 further expanded accessibility to more isolated mountain villages (Li 54). This may have been the first time northern Japan had access to new, unused cotton. While boro were not exclusively made from cotton, the majority of extant boro are either made of cotton or have cotton patches layered on the interiors to make them more insulating and comfortable (Wada 280).

It is possible that boro made from less desirable bast fibres were the first to be discarded, explaining why boro, which only started being preserved in the late 1900s, are predominantly but not exclusively cotton.

This cotton rag trade was sustained by the many benefits that cotton brought the Japanese working class. In addition to warmer clothing, cotton heavily impacted the home in the form of bedding. Where previously common folk would sleep on wooden floors with straw mats and paper futons stuffed with straw and cattail, “the later use of cotton batting was a revolutionary improvement in sleeping comfort” (Wada 281). Many extant boro featured in museum collections and print are futon, quilts, and comforters, where the beddings featured some of the most dramatic patchwork (Wada 279, Schwartz-Clauss and Szczepanek). Since textiles were often kept within families for multiple generations, a single textile could contain pieces from other family members or patches acquired through trade and relationships, adding to the sentimental charm often seen in contemporary rhetoric on boro (Fig. 2).

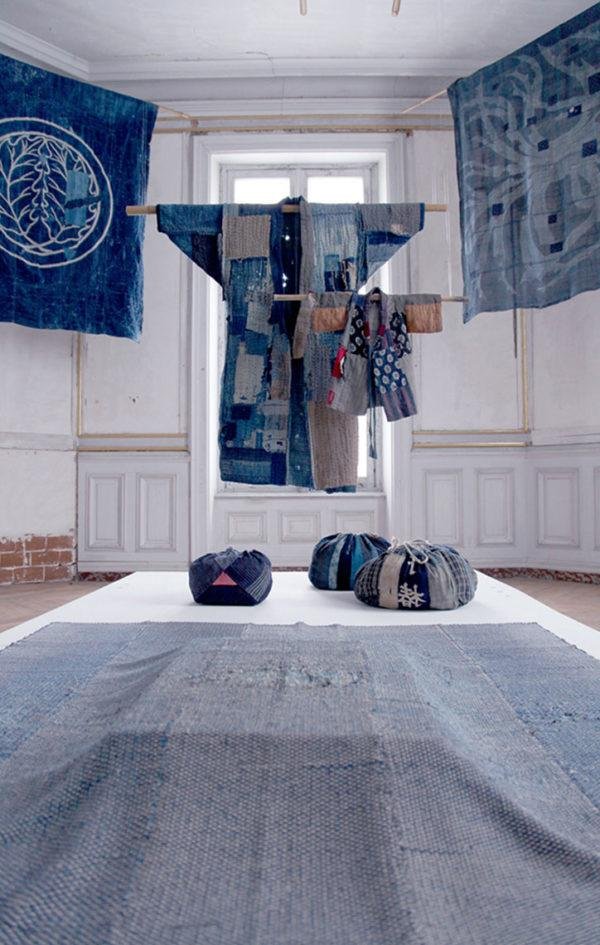

Figure 1

Museum display of various boro, 2013, cotton, Boisbuchet, France. (Schwartz-Clauss and Szczepanek) © Grégoire Basdevant, copyright: CIRECA / Domaine de Boisbuchet 2013, used with permission.

Figure 2

Bed Comforter, Dec 27, 2016, hemp warp, cotton weft, and stuffed with old work clothing, Amuse Museum, Tokyo. (Ide) © Keisuke Fukamizu, copyright: Visvim 2016.

Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, Japan experienced a multi-factored improvement in living standards for the working class, alongside a more productive and accessible textile industry (Nakamura 25-27).

Although firsthand accounts of poor families prior to the twentieth century are rare or untranslated, it is clear that the necessity of boro was deprioritized for a time in favour of the economic benefits that industrialization provided (Schwartz-Clauss and Szczepanek, Ide). As a result, families likely disposed of or stored away their boro. The volume of disposed boro, their composition, uses, history, and values, will unfortunately never be certain.

The remaining identifying trait of boro is indigo dye, which began during the Heian period (794-1185) or possibly as early as the fifth century AD, when Japan began cultivating it locally (Embassy of Japan in the UK, Balfour-Paul 26). At first, only the imperial elite had access to the dye, but during the Edo period (1600-1868), both indigo and cotton crops benefited from a developing fish trade. The by-product of fishmeal—ground and cooked fish skin—increased crop yield through its use as a fertilizer, making indigo a common dye among rural Japanese workers (Wada 280, Balfour-Paul 186). The effectiveness of indigo dye on cotton and bast fibres meant that many cotton garments, as well as the rags that they produced, were dyed with it. Indigo dye was so prevalent in Japan that British chemist R.K Atkinson named the colour “Japan Blue” (Embassy of Japan in the UK). Extant boro often display the multiple patterns of traditional dye techniques available at the time, as well as the many shades and depths of blue and green that natural indigo could achieve through different dye techniques. I theorize that it was occasionally used to help achieve uniformity in boro, either by piecing solid indigo pieces together or by garment dyeing a patched work.

Despite a contemporary appreciation, prior to the 21st century boro was for many a sign of poverty born of material scarcity and in opposition to the patch-free garments of the societal elite. This could have been why patches were often layered on the interior of garments, in some instances for comfort, but possibly to hide them as well. Contemporary displays of boro textiles will frequently showcase either the wrong side of boro sheets or lay open the interiors of garments to display the more visible handwork, such as with the kimono in Fig. 3, which has the front panels pulled open to display in the patchwork inside. That is not to say that artistic pattern contrasts were not used on the exteriors of garments, especially in instances of piecing, but often these garments utilized larger pieces with more stark contrast. Wada notes, “The laboriously sewn, evenly sized strips of one boro contrast with the practical, strategic placement of scraps-over-holes in another” (Wada 283). As with any art, a wide spectrum of examples exists with a variety of expressive and utilitarian choices made under unique social and economic circumstances.

Figure 3

Boro kimono displayed open, 2013, cotton, Boisbuchet, France. (Schwartz-Clauss and Szczepanek) © Deidi von Schaewen, copyright: CIRECA / Domaine de Boisbuchet 2013.

Boro has a complex history. At its simplest, parts of a garment could be composed of pieced-together off-cuts, extending fabric that would otherwise have been too small. Taken to the extreme, however, a multi-generational garment made from pieced-together off-cuts could be heavily repaired with patches layered over other patches—those patches themselves taken from other boro, each with their own patches and piecework.

Rectangular patchwork, indigo dye, cotton, and bast fibres, as well as a labour-intensive nature, as noted above, are so consistent in boro because of the conditions that made them the only available options in an economy that, for the lower classes, was resource-poor but had a labour surplus (Nakamura 25). With the working class now cotton-clad and indigo-dyed, societal elites shifted their attention to fine ramie fibres dyed purple from rare roots. However, that purple was often faked by combining the red dye of sappanwood with indigo (Balfour-Paul 186).

While grounded in social stratification, boro have a unique aesthetic appeal in their intricate handwork and laborious repair that contrasts strongly with modern fashion’s material abundance. The handwork and time spent created countless unique pieces, many lost to time as boro were often seen as a shameful display of poverty and discarded or hidden with the acquisition of new articles. Boro were not appreciated until long after their utility had disappeared, and renewed interest finally gave them a name they never previously had, from the onomatopoeia “boroboro,” which means something tattered or repaired (Schwartz-Clauss and Szczepanek). This is a naming convention that is also at odds with the casual usage of the word boro to mean “rags” (Horikiri xviii).

While boro was introduced to English audiences through its contemporary global definition as art, in Japanese, the word has a longer history with more individual associations. Boro, as a word, has a unique imprint upon certain Japanese audiences: what boro they had seen and potentially possessed in their family, and a reconciliation with a currently shifting definition towards craftsmanship and sustainability, from a word that literally means “rags.” In The Stories Clothes Tell: Voices of Working Class Japan, author Tatsuichi Horikiri and translator Rieko Wagoner do not directly engage with the contemporary definition of boro. At the very least, they reject the dismissal and reduction of individual garments into a single category in an effort to highlight the individuality of each piece and reconcile their uniqueness with the working-class conditions that make them special. The boro in my possession has been worn from potentially generations of use, removed from its origin and its future interactions, and placed under my care—a situation that may disappoint an archivist such as Horikiri.

Workers did not address their repaired cloths with the name boro, since the heavy repairs and details would not have been unique but standard practice for their contemporaries.

The entity we now call boro is only so unique because it demonstrates how disparate groups suffered under the same systems and found the same solutions: the hand-stitched solutions of those who barely got by at the bottom by crafting and repairing garments with scraps.

Boro Object Analysis

An object analysis of a boro in my possession (referred to throughout as “this boro” to distinguish it from other boro) follows as a companion to the history of boro, along with other contemporary examples. This boro was purchased from a vintage store in Toronto, Coffee and Clothing, where it was described as being made of indigo-dyed hemp and was dated to sometime during the Meiji era (1868- 1912), though no documentation was provided to prove authenticity. It is a rectangular sheet pieced together from three smaller rectangular pieces: one larger sheet and two others of matched widths that are in a slightly greener indigo hue than the large piece (Fig. 4 and 7). Both sides feature the selvedge (self-edge) characteristic of hand-loomed fabrics, where the weft yarns wrap around the edge and therefore do not require finishing to prevent unravelling (Fig. 5). The top and bottom edges are rolled twice and secured with a straight stitch, hiding the raw fabric edge within the roll. The seams connecting the pieces are similarly secured with a straight stitch but with a smaller stitch width, likely for strength. Though the raw fabric edges where the pieces are connected are left exposed, the seam allowance is folded away from the largest piece and secured by a top stitch with a longer stitch width, similar to the one securing the rolled edges (Fig. 7).

Figure 4

Larsen, Eric, Boro front, 2023, digital photography, Toronto.

The hemp yarns have a stiff, dry hand, though the areas closer to the centre have softened and lightened in colour with use. Signs of use can also be seen on the abraded surface, with threadbare sections and prominent pilling on both sides of the fabric. It has a plain weave and some mild slub consistent with hand-spun yarns. The loose yarns fray to reveal a slight silver sheen at the core, where the dye did not penetrate as effectively (Fig. 5 and 6). The threads holding the boro together are a darker charcoal colour, as opposed to the blue-green indigo of the rest of the piece, and are softer to the touch than the boro yarns, suggesting they may be cotton (Fig. 6). The threads are not knotted at the ends of seams, save for one, which is less of a knot and more of a ball that may have developed over time. Instead, the threads are secured with a single backstitch. Occasionally, two threads are knotted together in the middle of a seam, likely to join two threads that would otherwise have been too short (Fig. 6).

The largest piece features two distinct areas of wear: one darker with less wear, and the other faded from abrasion. The wear so rectangular in shape, and the separation so stark, that it almost appears to be two separate pieces (Fig. 4). The smallest piece features a distinct rectangular fade pattern on the side without the seam allowance folded into it, and the last piece features the heaviest wear, including a threadbare section which connects to an undamaged section of the largest piece (Fig. 7). These fade patterns suggest that this fabric has been used in previous garments or is from a garment that has seen significant wear. Throughout the boro, there are stains in various shades of yellow, brown, and grey. There is no noticeable smell or odour coming from the textile, possibly due to age or preparation for resale.

The Boro As A Worn Object

Boro, in general, are essentially defined by the state of their wear, with the often human-shaped wear patterns accentuated by rectangular patches and geometric patterns. However, this boro in particular exhibits a less clear wear pattern and, in its current form as a rectangle with finished edges the size of a handkerchief, an unclear intended use. By analyzing it through the framework with which Ellen Sampson uses to observe footwear in Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear, we can explore the possible origins of its wear. In addition to Sampson’s work, Tatsuichi Horikiri in The Stories Clothes Tell: Voices of Working Class Japan provides invaluable insights into the living and working conditions of the working class through various garments and textiles, as well as interviews with their owners. Many examples feature patchwork and repair that are not labeled as boro, but the breadth of garments featured, their uses, and the ways in which they were repaired add nuance and individual histories often unmentioned in collections of boro where provenance is difficult to trace.

THE BORO AS ARMOUR

While “the empty shoe always alludes to its missing binary: the foot” (Sampson 76), this boro lacks a direct analog. However, its size could allude to the situations in which it may serve as armour. Being smaller in size, it is possible that it performed protective duties of a handheld nature, such as the protective layer between a hand and a rough farming tool or as an insulating layer between a hand and a hot cooking vessel. Sampson highlights the nature of a shoe to become polluted by wear, to be dirtied by the environment through use and the excretions of the user, and this boro, through its stains, pills, and holes, reflects that nature (Sampson 76). The use of this boro as armour is not as a garment or insulation from the cold. As the prevalence of cotton boro that are softer and more insulating indicate, hemp and other bast fibre boro, if still in use, would likely have moved away from applications where they were no longer preferable or ideal, and used instead as patches, netting, or coverings.

An example of one such use comes from a textile featured in The Stories Clothes Tell: a mosquito net made of loosely woven hemp and featuring large panels pieced together from smaller ones. While this boro is too small to function as a traditional Japanese mosquito net (the featured net was a large square basket that reached from floor to ceiling and could fit up to four sleeping persons, similar to a large mesh tent), it could be used as a protective layer for exposed skin (Horikiri 39-42). It might have covered the back of the neck during outdoor work by being secured to a hat or head covering. Similarly, it could have been used as a window covering to allow for light and airflow while protecting inhabitants against bugs or wildlife.

Figure 5

Larsen, Eric, Boro corner, 2023, digital photography, Toronto.

Figure 6

Larsen, Eric, Boro reverse-side stitching details, 2023, digital photography, Toronto.

INTERACTION BETWEEN THE BODY, INDEBTEDNESS, AND BORO

Sampson indicates that the shoe imprints onto the body just as the body imprints onto the shoe (Sampson 80-86). So, what do the imprints on this boro indicate of the bodies that used it?

The pilling and staining on this boro are concentrated at the centre (Fig. 8). This could result from hands or materials rubbing against it, or from wrapping it around something. The holes that have formed within this boro may also indicate a repeated, specific use, as the majority are formed from broken warp (vertical) yarns. In the case of a window or neck covering, it may have received a repetitive strain from being secured at the top and pulled downward, leading to the sagging that this boro has in the centre when held upright.

THE INCORPORATED BORO

Sampson writes, “The shoe, as part of the bodily schema, holds a curious position: both incorporated into the self and materially separate from it,” acting as a mediator, intermediary, and filter through which the world is experienced (Sampson 92). Where the shoe serves this role for the foot, boro serves multifaceted and multidisciplinary roles, potentially being incorporated into any garment for any use. With the ability to filter the experiences of labour, sleep, and leisure through garments, bedding, and tools, boro overall had an almost unavoidable impact on the experience of the working class—not just as a reminder of class and scarcity, but as a connection to past and present family members and imprinted uses. Boro can partially achieve this through the breadth of its definition; a textile that evades strictly defined characteristics encourages almost limitless possibilities for attachment. Boro is essentially defined by its incorporation: scraps sewn into damaged garments to make them whole and incorporated into one another, becoming greater than the sum of their parts. However, each boro achieves an identity all its own through of its unique aesthetic and history. While boro as a category is contemporarily heralded as a sustainable expression of craftsmanship, the families that created them almost certainly had boro that they loved and boro they did not hesitate to discard at first opportunity.

Since boro were created as a laborious solution to material scarcity, sentimental attachment to boro was not guaranteed. As a model for modern sustainability, boro serves as an imperfect template, as it is possible that less desirable materials were pieced together, yielding less desirable boro. These were likely the first to be replaced by boro of more desirable materials or disposed of as materials became more abundant and accessible. This boro, made of small panels of more irritable and less insulative hemp compared to softer and more comfortable cotton, may have been one of the first boro to be disposed of or replaced. Its incorporation into the bodies of new garments or into the routines or homes of the working class at eventually ended and found its way into my possession, possibly through disposal.

Boro, for that reason, is an imperfect template for sustainability, and even historically ended in the generation of waste, such as this hemp boro, even if it is now perceived as collectible.

While boro has thus far been treated as a unified concept, not everyone treats boro as a collective artform under that name. Horikiri, despite honouring a collection of heavily repaired garments, says, “I would never call the items in my collection boro (rags), no matter how worn out or dirty they may be, nor would I ever let anyone else call them that” (Horikiri 7). Although initially published in a magazine in the 1980s, before the unification of repaired textiles under the contemporary definition of boro, the translator of The Stories Clothes Tell, Reiko Wagoner, notes in the introduction that a 2002 Japanese publication addressed the disconnect between “boro” as a common word for rags and the heavily repaired textiles that now bear the same name (Horikiri xviii). While the translation of Horikiri’s work was published in 2016, the nuance with which the word boro is treated is unlike many other sources on the subject. A review of the book notes that not only is Horikiri’s “bottom-up history” a valuable academic text on Japan, but Wagoner’s translation shows considerable skill and accuracy in addressing the subject matter (Chaiklin 302-303). While incredibly subjective, Horikiri and Wagoner place increased value on the individual stories behind each piece rather than placing focus on the term “boro.”

Figure 7

Larsen, Eric, Small boro panel, 2023, digital photography, Toronto.

Figure 8

Larsen, Eric, Staining, pilling, and fading on boro 2023, digital photography, Toronto.

THE BORO THROUGH THE LENS OF WHAT’S THE USE?

In What’s the Use?: On the Uses of Use, philosopher Sara Ahmed explores the many variations and technicalities of the word “use” in common language. Both Ahmed and Sampson draw attention to the idea that an object can disappear into use, become an extension of the self, or a serve as a necessary intermediary through which to experience the world (Ahmed 21, Sampson 73). Although boro today are being removed from active use for collection and preservation, this boro, and its particular state of use, can be assessed through Ahmed’s various labels for states of use, beginning with the most straightforward: an item in use.

THIS BORO IN USE

This boro is not currently in use in line with any of its original utilitarian purposes, neither as a garment nor as a textile, but rather as a collectible. Prior to my purchase of it, this boro was in use as a commodity. Using the definition of a commodity provided by Prabhat Patnaik in a volume of Social Scientist, Patnaik says of commodities that, “The true specificity of a commodity consists in the fact that while it is both a use value and an exchange value for the buyer, it ceases to be a use-value for the seller for whom it is pure exchange value, a pure representative of a certain sum of money (or command over other commodities)” (3-4). Use value speaks to the properties and values of an item that are not monetary, and this boro entered a market that trades in vintage goods, where it was assigned an exchange value. As this boro is hemp, and therefore would not have been a part of the cotton rag trade that generated many cotton boro, its entrance into a market for vintage goods was possibly the first time it had been in use within a capitalist system, and what often follows items that were in use is that they become out of use.

The Boro Out of use

Boro is almost defined by how it refuses to be put out of use, with patches placed over other patches to keep garments in use in perpetuity. When technical advancements lead to an increased availability of textiles and boro started suggesting a status of poverty, boro were put out of use, discarded, or stored away. However, this boro, like many others, has been repurposed and put to use as a collectible or as a subject for preservation and appreciation. Unable to be put out of use through wearing, any situation in which it might lose value depends upon cultural values. To draw on Silas’ broken pot, which Ahmed alludes to, a clay pot that, once broken, is no longer in use but placed aside as a memorial; to see it refuse to be put out of use in the same fashion as boro would involve partially repairing the pot to continue to hold smaller amounts of water, refashioning it into digging tools and arrowheads, or grinding it into a paste for building blocks (Ahmed 32). In this sense, the pot, and boro in general, can be said to represent a queer use, with intended uses shifting between persons, garments, and tasks. As Ahmed says of queer use, “when things are used for purposes other than the ones for which they were intended, [they] still reference the qualities of things, queer use may linger on those qualities, rendering them all the more lively” (Ahmed 26).

THE BORO USED, OVERUSED, AND USED UP

The following definitions that Ahmed provides for use explore the stages beyond use. This boro is used, extensively used, and carries with it many signs of use such as holes, stains, and dye loss. It is perhaps overused, as it is comprised of scraps, becoming increasingly tattered and defined by the more worn parts of it that were discarded to allow it to live in its current form. In discussing the idea of a used table, Ahmed regards, “We might think of the scratches left behind from use not as signs of degradation or the loss of value but as a testimony. The table might testify to its own history” (Ahmed 37). Boro overall, as well as this boro, inhabit this space where being used can be seen as a value addition, proof of work, what some may call a patina, a positive sign of use. This contrasts with the previous example Ahmed provided of the table being worn down and over-exploited. While a table may still serve a functional purpose, this boro is at once used, overused, and used up. But what use could this boro provide to its new home once removed from the shop (Ahmed 38)? One option is as a collectible, appropriate for an item that is used, overused, and used up.

There is an old Japanese saying that relates to the early twentieth-century Japanese philosophy of mottainai (no-waste): “You shouldn’t throw away any piece of cloth big enough to wrap three beans” (Li 54). While likely not meant to be taken literally, we can take it literally to speculate on a possible use for this boro as a net for gathering beans. This boro would be overused in the way that Ahmed defines it, used to the point that further use becomes more challenging (Ahmed 48-49). It features wear and holes that would make handling beans require additional care and caution; certain beans would certainly slip through. We can only hope that the creators of this boro harvested soybeans and not lentils. However, if the boro continued its use as a bean net, the holes could be patched up to allow for further use.

What would it take, then, for a boro to become used up? If a boro could be used up, it would require extreme circumstances. Even the creators of this boro refused, up to a point, to put out of use a piece barely larger than my hand—a piece made of less insulating and coarser hemp rather than the more valuable cotton. If this boro was in use up to the late Meiji era, what situation would its creators have been in to hold onto it for so long, that up until 1912 a tattered hemp rectangle, stretched and beaten out of shape, was deemed irreplaceable? To restrict boro as a sign of inescapable poverty or extreme sentiment belies the fact that it was boro as a concept—textiles being overused themselves—that was ultimately used up.

THE BORO UNUSED

Ahmed’s final notion of use is unused—an item without use. Boro, as traditionally defined, cannot be unused; it cannot be new, as it requires use and repair to exist as boro. However, where extant examples of boro come from museums and collections, an unused boro would have to come from an entirely different context. One such example comes from KUON, a Japanese brand existing exclusively in uppercase. It created a collection that not only is boro-inspired, but contains pieces made of authentic boro (Fig. 9). These artifacts from the nineteenth century are crafted into garments that, prior to purchase or wearing, remain unused. The brand also created “upcycled boro” crafted from their own textile waste, though the difference in authenticity is reflected in their costs: $9,345 for authentic boro and $1,682 for the upcycled version, despite the latter being made of black silk (Li 55-58).

Boro are used, overused, and at one point, used up, but have been brought back as collectibles, artifacts, and now as a philosophy akin to mottainai. This philosophy includes not just the repair of garments but also the unused boro garments of KUON. This boro inhabits all these states simultaneously; were it to be made into a laptop sleeve, used to patch a torn garment, or incorporated into a wardrobe, it would once again refuse to be put out of use and even become unused once again. If I have learned anything from the history of boro, the appreciation of its craftsmanship, and its ascension from a symbol of poverty into a cultural landmark, it is that this boro will not be best respected or appreciated in a display case, hung on a wall, or discarded. Instead, its next stage of use—whatever form that may take—will be its most lively.

Figure 9

KUON, Boro Blazer, KUON jacket made from authentic boro, Apr 24, 2023, cotton, KUON. (Li) © KUON 2016.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. “What’s the Use?” On the Uses of Use. Duke University Press, 2019.

Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo. British Museum Press, 1998.

Chaiklin, Martha. “Review of The Stories Clothes Tell: Voices of Working- Class Japan, by Tatsuichi Horikiri.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 73, no. 2, 2018, 302-304. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/mni.2081.0016.

Embassy of Japan in the UK. Aizome (indigo-dyeing): A Brief History of Aizome. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2014. https://www.uk.emb japan.go.jp/itpr_en/2306aizome.html#:~:text=It%20made%20its%20way%20into,at%20various%20points%20in%20history.

Horikiri, Tatsuichi. The Stories Clothes Tell: Voices of Working-Class Japan. Translated by Rieko Wagoner. Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.

Ide, Kosuke. “Survey: Boro.” visvim.tv, web.archive.org/web/20170107001313/ https://www.visvim.tv/dissertations/survey_boro.html

Li, Leren. “Refashioning Repair Culture Through the Circle of Value Creation: A Case Study of the Japanese Brand KUON.” International Journal of Sustainable Fashion & Textiles, vol. 2, no. 1, 2023, 53–62. https://doi.org/ 10.1386/sft_00020_1.

Nakamura, Naofumi. “Reconsidering the Japanese Industrial Revolution: Local Entrepreneurs in the Cotton Textile Industry during the Meiji Era.” Social Science Japan Journal, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, 23–44. JSTOR, http://www. jstor.org/stable/43920466. Accessed 24 Nov. 2023.

Patnaik, Prabhat. “Culture and Commodities.” Social Scientist, vol. 43, no. 7/8, 2015, 3–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24642355. Accessed 24 Nov. 2023.

Sampson, Ellen. Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Schwartz-Clauss, Mathias, and Stephen Szczepanek. “Boro–the Fabric of Life | Domaine De Boisbuchet.” Domaine De Boisbuchet, 24 May 2019, www. boisbuchet.org/exhibitions/boro-the-fabric-of-life.

Wada, Yoshiko Iwamoto. “Boro No Bi: Beauty in Humility — Repaired Cotton Rags of Old Japan.” DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln,digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/458.

Author Bio

Eric Larsen is a Master's of Fashion student at Toronto Metropolitan University. They are an apprentice bespoke shoemaker and focus their research on the history of denim, workwear, tailoring, and the dress habits of the working class. They believe that clothes look best when they have signs of wear and repair and hope that you, dear reader, will repair something in the near future.

Article Citation

Larsen, Eric. “Something Boro’d, Something Blue: An Analysis of Japanese Repair Practices and Material Scarcity.” Fashioning Sustainment, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.38055/FST030102.

Copyright © 2024 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)