Review: Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion

by Julia Skelly

abstract

The Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion exhibition at Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ) is a celebration of Alexander McQueen's impact on the fashion industry from 1990 to 2010. Originally presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and curated by Clarissa M. Esguerra, the exhibition showcases sixty-nine iconic McQueen pieces sourced from Regina J. Drucker's private collection. This assembly, complemented by contributions from LACMA, MNBAQ, and sculptural works by Michael Schmidt, is structured around four central themes: Mythos, Fashioned Narratives, Technique and Innovation, and Evolution and Existence. This review explores McQueen's fusion of religion, mythology, and storytelling evident in the featured ensembles, as well as his skillful combination of innovation and craftsmanship. The author invites critical examination of the exhibition's curatorial intent, particularly in the ‘Fashioned Narratives' section, raising important questions about representation, colonialism, and cultural sensitivity in Western museums. The comprehensive showcase of McQueen's ensembles is discussed in juxtaposition to historical paintings, contemporary multimedia, and an array of unique artifacts. As a result, the exhibition offers a multifaceted exploration of McQueen's legacy, inviting audiences to engage with an intricate interplay of art and fashion while fostering contemplation on representation and diverse artistic influences.

Volume 4, Issue 2, Article 3

Keywords

Fashion

Art

Appropriation

Craftsmanship

Beauty

-

https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040203

-

Skelly, Julia. “Review: Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion.” Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1-15, DOI: 10.38055/FS040203.

-

Skelly, J. (2023). Review: Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion. Fashion Studies, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.38055/fs040203

-

Skelly, Julia. “Review: Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion.” Fashion Studies 4, no. 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.38055/fs040203.

Drunk on beauty. That’s the best way I can describe the impact of Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ), which is the first retrospective of McQueen’s fashion in Canada. The draping! The materials! The most perfect pocket I’ve ever seen! (On a red swath of a dress with the famous birds motif, no less.) Flapper dresses that would make Zelda Fitzgerald swoon (Figure 1). Almost every outfit had me hissing “Stunning!” under my breath.

Organized by, and originally shown at, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) under the title Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse, the show was curated by Clarissa M. Esguerra, Associate Curator in the Department of Costume and Textiles at LACMA.

Figure 1

Left: Frans Pourbus II, Portrait of Louis XIII, King of France, as a Child, circa 1616, oil on canvas, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. William May Garland, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Right: Alexander McQueen, Women’s Dress and Shoes from the Widows of Culloden Collection, Fall/Winter 2006–2007, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift from the Regina J. Drucker Collection in loving memory of Joseph and Genevieve Venegas, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

In Los Angeles, the show included 195 artworks (including the McQueen pieces) from the LACMA collection, and in the Quebec City iteration, there are a number of works loaned from the LACMA alongside thirty-two works from the MNBAQ’s collection. In addition, there are seven sculptural headdresses and pairs of shoes created by Los Angeles artist Michael Schmidt.

Figure 2

Left: Manuel Cipriano Gomes Mafra, Urn, circa 1865-1887, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Barbara Barbara and Marty Frenkel, photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Right: Alexander McQueen, Women’s Ensemble (detail) from Plato’s Atlantis Collection, Spring/Summer 2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift from the Regina J. Drucker Collection, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

The accompanying artworks include several religious paintings, as well as an exquisite glazed earthenware urn (c.1865–1887, LACMA) by Portuguese artist Manuel Cipriano Gomes Mafra that is positioned alongside several dresses (one with the “Reptilia” print, another with a moth print) from the Plato’s Atlantis collection (Spring/Summer 2010; Figure 2 and Figure 3). Plato’s Atlantis was McQueen’s last fully-realized collection before he died by suicide in 2010. Fittingly, the clothes from that collection appear in the exhibition’s last room, which also has a two-minute clip from James Cameron’s underwater film The Abyss (1989) projected on a wall, the colours of which echo the colour scheme of the McQueen dresses. The film clip provides a fittingly epic musical accompaniment to the clothing. Notably, several of the mannequins wear the collection’s “Titanic” shoe design. According to the curators: “In McQueen’s handling, the cautionary tale of the Titanic warns of impending repercussions for continued human destruction of the environment.”[1]

[1] Exhibition catalogue, 161.

Figure 3

Installation view of two dresses from the Plato’s Atlantis collection (Spring/Summer 2010), a large oval rustic dish (France, c. 1600-50) with a snake design, and Manuel Cipriano Gomes Mafra’s earthenware urn (c. 1865-87), which is adorned with a three-dimensional frog and lizard. Photo: MNBAQ. Denis Legendre.

Anyone who knows McQueen’s work is going to go into the exhibition aware that the clothes will be breathtaking in both appearance and craftmanship. Indeed, on one of the walls is a McQueen quotation in large letters that reads: “The basis for everything I do is craftmanship.” McQueen famously trained in Savile Row tailoring early in his career, and his precise knowledge of how to cut cloth is everywhere evident in the show.[2] Another quotation on another wall states that McQueen was not the kind of designer who sat back and removed himself from the making aspect of design; he wanted to feel, touch, and cut the cloth himself, whether for a dress or for his infamous “bumster” trouser, which provide a tantalizing glimpse of the top of the wearer’s buttocks.

Interestingly, while there are a few outfits informed by McQueen’s Scottish heritage (Figure 4), which are positioned in front of a larger-than-life portrait of Hugh Montgomerie by John Singleton Copley (1780), there is no garment from the controversial collection entitled Highland Rape (Fall/Winter 1995–1996). When the Highland Rape runway show first took place, McQueen was accused of misogyny. Fashion historian Caroline Evans argues in her article “Desire and Dread: Alexander McQueen and the Contemporary Femme Fatale” that the collection does not victimize its wearers, but rather provides armour for the modern woman. This, at least, was how McQueen conceptualized the clothing. As Evans observes:

…it was the styling and presentation of McQueen’s fifth collection, Highland Rape, shown in March 1995 and his first show to be staged under the aegis of the British Fashion Council in its official tent during London Fashion Week, which attracted the greatest criticism… On a runway strewn with heather bracken McQueen’s staggering and blood-spattered models appeared wild and distraught, their breasts and bottoms exposed in tattered laces and torn suedes, jackets with missing sleeves, and skin-tight rubber trousers and skirts cut so low at the hip they seemed to defy gravity.[3]

[2] Clarissa M. Esguerra and Michaela Hansen, “Introduction,” in Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind Mythos Muse, exhibition catalogue (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2023), 11.

[3] Caroline Evans, “Desire and Dread: Alexander McQueen and the Contemporary Femme Fatale,” in Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wilson (eds), Body Dressing (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 202.

Figure 4

Installation view of two ensembles from the Widows of Culloden collection (Fall/Winter 2006–2007). Photo: MNBAQ. Denis Legendre.

Critics at the time described the show as “aggressive and disturbing,”[4] but according to McQueen, the runway performance was meant to “show that the war between the Scottish and the English was basically genocide.”[5] Evans proposes that the clothes and show are not misogynist, but rather construct a femme fatale figure: “Allying glamour with fear rather than allure, McQueen’s avowed intent was to create a woman ‘who looks so fabulous you wouldn’t dare lay a hand on her,’ a statement which was illuminated by the knowledge that one of his sisters had been the victim of domestic violence.”[6] Evans adds that, “Medusa-like, McQueen’s woman was designed to petrify her audience, dressing if not actually to repel or disgust, at least to keep men at a distance, rather than to attract them.”[7] The Quebec exhibition does not foreground this aspect of McQueen’s designs; the pieces are displayed in order to underscore their seductive beauty, rather than any sense of the threatening femme fatale. Nonetheless, given the sculptural nature of some of the clothes, one can imagine feeling armoured when wearing them.

[4] Quoted in ibid.

[5] Quoted in ibid.

[6] Ibid., 206.

[7] Ibid., 206-207.

Figure 5a

Installation view of woman’s dress from the Untitled (Angels and Demons) collection (Fall/Winter 2010-11). The dress hangs beside Jan Mandijn’s painting Saint Christopher and the Christ Child (c. 1550). Photo: MNBAQ. Denis Legendre.

Each room has multiple McQueen pieces and artworks, some historical and some contemporary. For instance, in the first room (Mythos), the viewer is initially faced with a dress (Figure 5A)[8] that is digitally imprinted with photographs of Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych comprised of The Temptations of Saint Anthony, The Last Judgment, and The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1482).[9] Next to this dress is a small painting by Flemish artist Jan Mandijn entitled Saint Christopher and the Christ Child (c. 1550, LACMA), which depicts, among other things, a decapitated head of a bearded man hung from a tree branch by his top knot and with a cleaver embedded in his skull. A Bosch-like devilish creature with a tiny spear is shown in the background crawling on what appears to be a cracked-open egg (Figure 5B). Next to the painting is an etching by Pieter van der Heyden, after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, entitled Envy (Invidia) from 1558. This strange little work also features monstrous creatures and grotesque humans, and indeed Bruegel was influenced by Bosch, as was McQueen.[10]

[8] Alexander McQueen, Woman’s Dress, from the Untitled (Angels and Demons) collection, Fall/Winter 2010-2011. Exhibition catalogue, 27.

[9] The photographs were digitally composited and woven in jacquard.

[10] Erin Sullivan Maynes, “Envy (Invidia),” in exhibition catalogue, 28.

FIgure 5b

Woman’s dress from the Untitled (Angels and Demons) collection (Fall/Winter 2010-11). Photo by author.

The exhibition does an excellent job of illuminating the wide range of visual influences on McQueen’s body of work, displaying, for instance, nine aquatints from the LACMA collection by Pablo Picasso from 1959 that depict bull fighting, and an etching of the same subject by Francisco de Goya entitled A Spanish Knight Kills the Bull after Having Lost His Horse (1816, LACMA), in a room dedicated to McQueen’s bull fighting collection, The Dance of the Twisted Bull (Spring/Summer 2002).

Given that curators and museum scholars are increasingly asking how to decolonize the museum, I consider and critique the second room of the exhibition (Fashioned Narratives) through a postcolonial lens. This room includes the forementioned Scottish-influenced outfits, but also a white fur ensemble (Scanners collection, Fall/Winter 2003–2024; Figure 6) influenced by Siberian clothing, and a kimono-inspired jacket that could be described as chinoiserie and categorized as cultural appropriation (Scanners collection), regardless of McQueen’s intentions to celebrate Siberian innovation for cold weather and Japanese textiles, respectively. McQueen envisioned Scanners as a journey across Siberia and Tibet that ended in Japan.[11] The curators in Quebec have presented these two outfits alongside an Inuit coat (amauti) by Nelly Putuguk and Siupi Junanasialuk (made in Nunavik in 1950 with caribou skin, ringed seal skin, glass beads, lead, tin, and ivory) and Asian textiles such as two green brocade (Kati Rimo) temple hangings produced in seventeenth-century Tibet in order to counter-act the culturally appropriative nature of McQueen’s designs.[12] However, the temple hangings raise the question of whether this kind of religious material culture should be exhibited in a western museum at all. In the same room are two dresses (Figure 7 and Figure 8) from the Fall/Winter 2007–2008 collection In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692, which are complemented by two remarkable woodcuts by German artist Ernst Barlach that were inspired by Goethe’s Faust, including one entitled Witch’s Ride (1922, published in 1923, LACMA).

figure 6

Woman’s ensemble (coat and skirt) from the Scanners collection (Fall/Winter 2003-4). Photo by author.

[11] Exhibition catalogue, 67.

[12] Anne Anlin Cheng addresses McQueen’s appropriation of Asian textiles and dress in her book Ornamentalism. See Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 88-96.

Figure 7

Woman’s dress made with silk satin and glass beads from the In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692 collection (Fall/Winter 2007-8). Photo by author.

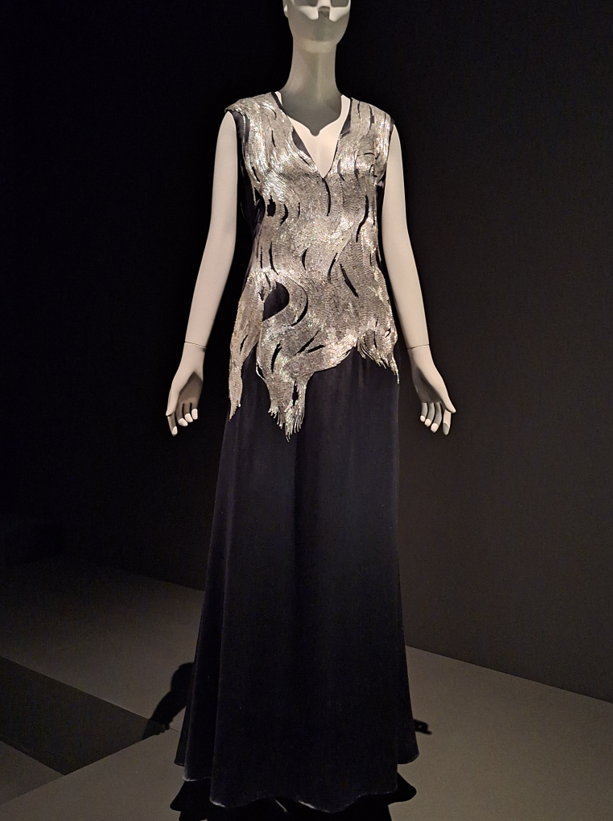

figure 8

Woman’s dress made with silk velvet and glass beads from the In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692 collection (Fall/Winter 2007-8). Photo by author.

One critique regarding the exhibition centers on this particular room: why combine Siberian- and Japanese-influenced clothing across from clothes inspired by the Salem witch trials of the seventeenth century, and next to Scottish-inspired ensembles from the Widows of Culloden collection (Fall/Winter 2006–2007)? McQueen was critical of colonialism and imperialism, which inspired several of his collections including The Widows of Culloden and The Girl Who Lived in the Tree (Fall/Winter 2008–2009).[13] Clarissa M. Esguerra and Michaela Hansen remark in the exhibition catalogue’s introduction that “it can be challenging to immediately differentiate the superficial appropriation of culture for commercial gain from cultural exchange or inspiration as a mode of appreciation of storytelling,” but they also acknowledge that “though [McQueen’s] intentions were to celebrate dress and culture outside his own, he lacked personal intimacy with the subject matter.”[14] The curatorial framework could be further fleshed out by pointing to the fact that all of these groups of people have been, at one time or another, pathologized and violently eradicated due to misogyny, racism, and xenophobia.

The third room (Technique and Innovation) includes clothing inspired by a wide range of historical references including Renaissance, Flemish and Dutch Old Master paintings,[15] and the Roaring Twenties. The accompanying artworks include historical dress, as well as a large portrait of a flapper, Emmanuel Fougerat’s Mrs. Frank Ethelort McKenna, née Yvonne Pérodeau (1924, MNBAQ), which is positioned next to one of the dresses with which I opened this review. The grey-green, sequined garment with rows of tulle in lace is from the What a Merry Go Round collection (Fall/Winter 2001–2002; Figure 9).

figure 9

Woman’s dress made with polyamide net, plastic sequins and silk and metallic-thread lace from the What a Merry Go Round collection (Fall/Winter 2001-2). Photo by author.

[13] Esquerra and Hansen, “Introduction,” 13-14.

[14] Ibid., 14.

[15] Ibid., 13.

figure 10

Woman’s red-and-black silk damask dress from The Horn of Plenty collection (Fall/Winter 2009-10). Photo by author.

The vestibule before the fourth and final room (Evolution and Existence), which includes the dresses from the Plato’s Atlantis collection (the premise of which was a post-global warming scenario in which humanity has been forced to adapt and survive underwater), displays McQueen’s outfits from The Dance of the Twisted Bull collection (Spring/Summer 2002). Just before that vestibule are a series of dresses including a deceptively simple black, long-sleeved dress superimposed by the shimmering face of McQueen’s muse Isabella Blow who died by suicide in 2007 (La Dame Bleue collection, Spring/Summer 2008), and the red, silk damask dress with the black bird motif (designed by Simon Ungless) from The Horn of Plenty collection (Fall/Winter 2009–2010; Figure 10), which critiqued overconsumption. The title of the collection also refers to the name of the pub where Jack the Ripper’s final victim was last seen.16 Next to that dress (the one that I would have worn home if I had my druthers), is an interesting contemporary work by the art group BGL entitled Good Night Darthy (2006, MNBAQ), which is a painted aluminum and plastic work positioned on the floor that appears to be the melted body of Darth Vader, part of his helmet still intact.

There is something for everyone in this exhibition, assuming that everyone loves McQueen’s clothing as much as I do. There are historical paintings and contemporary multimedia artworks. There are glazed earthenware urns and platters decorated with snakes, dresses inspired by eighteenth-century aristocrats, and photographs of models wearing McQueen’s clothes before and after his fashion shows. There is also a photograph of McQueen himself wearing a purple outfit (sans the head) that looks like a mascot costume. He is smiling at the camera, but we know, in hindsight, that McQueen had his demons. As a feminist art historian, I often caution my students to be wary of the phrase “great artist,” but I am one hundred per cent comfortable describing McQueen as a great artist, whose death robbed us of future masterpieces.

[16] Jack the Ripper was the inspiration for McQueen’s first collection. Exhibition catalogue, 133.

References

Cheng, Anne Anlin. Ornamentalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Esguerra, Clarissa M. and Michaela Hansen. “Introduction,” in Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind Mythos Muse (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2023), 11-17.

Evans, Caroline. “Desire and Dread: Alexander McQueen and the Contemporary Femme Fatale,” in Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wilson (eds), Body Dressing (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 201-14.

Author Bios

Dr. Julia Skelly is a specialist in nineteenth-century British art, queer/feminist art, ethics and photography, global contemporary art, craft, textiles, excess, decadence, and addiction.

Her publications include Wasted Looks: Addiction and British Visual Culture, 1751-1919 (Ashgate, 2014), The Uses of Excess in Visual and Material Culture, 1600–2010 (Ashgate, 2014), Radical Decadence: Excess in Contemporary Feminist Textiles and Craft (Bloomsbury, 2017), and Skin Crafts: Affect, Violence and Materiality in Global Contemporary Art (Bloomsbury, 2022). Skelly’s next book, Intersecting Threads: Cloth in Contemporary Queer, Feminist and Anti-Racist Art, is under advance contract with Bloomsbury Academic. Skelly is Assistant Professor (LTA) in the Department of Art History at Concordia University.

Article Citation

Skelly, Julia. “Review: Alexander McQueen: Art Meets Fashion.” Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1-15, DOI: 10.38055/FS040203.

Copyright © 2023 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)