It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand

By Alphonso McClendon

DOI: 10.38055/FS050102

MLA: McClendon, Alphonso. “It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

APA: McClendon, A. (2024). It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand. Fashion Studies, 5(1), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

Chicago: McClendon, Alphonso “It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand.” Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2024): 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 2

Keywords

Blackness

Consciousness

Fashion

HBCU

Jim Crow

Diversity

Inclusion

abstract

Subversive idiom, cultural code, improvisation, and social agency are descriptors for a racial signification of the twentieth century that is closely tied to the African American experience in the United States. Within various decades, familiar cultural expressions became widespread, providing context to affirmations of blackness. Phrases such as “It’s a Black thing you wouldn’t understand,” “Black by popular demand,” and “Young gifted and Black” were prominent in Black communities, disseminated through apparel, literature, and lyrics. Often linked to musical developments, specific performers, and literary authors, these adages signified widely accepted cultural truths among Black people in America. In his conclusions regarding representation, meaning, and language, Stuart Hall (2012, p. 62) wrote of these “concepts and classifications of the culture which we carry around with us in our heads” that act as “our fantasies, desires and imaginings.” Hall argued:

And the advantage of language is that our thoughts about the world need not remain exclusive to us, and silent. We can translate them into language, make them ‘speak’, through the use of signs which stand for them—and thus talk, write, communicate about them to others (2012, p. 62).

Furthermore, this expressive language acted as a shared testimonial akin to the call-and-response form in early African music that engendered a participatory reaction by spectators. Thus, these words served as code for a unique experience along racial lines where individuals responded in agreement. Similar agency has been demonstrated throughout the Black struggle for equality in the United States. Artistic declarations in literature, music, and film emphasizing Black consciousness proliferated in the twentieth century. Exemplars of this period, including Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” and Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, advanced new cultural insights.

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement and its own cultural and racial indifference, the fashion industry in America, inclusive of businesses engaged with fashion goods and services, responded to a lack of inclusivity by attempting to better understand and support Black culture, employees, consumers, and brands. Especially, those organizations leading the design, marketing, and retailing of fashion had both individual and collective responses. This was evident in the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s IMPACT initiative, which “addresses the decades-long system of exclusion of Black talent in the industry with hopes to create a blueprint for other industries to follow” (CFDA, 2022). A mapping and contextualization of Blackness and Black-owned consciousness, alongside the fashion industry’s measures to improve diversity, will inform this intersection and phenomenon within American culture.

Agency of Blackness

Throughout the twentieth century in the United States, declarations of Black cultural knowledge have been evident in music, behavior, and dress. Louis Armstrong signaled the oppression in society with his recording of “(What Did I Do to be So) Black and Blue?” composed by Fats Waller with lyrics by Harry Brooks and Andy Razaf. The song gained popularity through the Broadway production of Hot Chocolates in 1929. The lyrics depicted a Black man facing financial and social challenges in life due to his dark skin: “I'm white inside, but that don't help my case, cause I can't hide what is in (on) my face” (Waller et al., 1992). Although infused with self-loathing, the song transcends individual suffering, calling the audience to unite in a shared feeling of being Black and blue: “How will it end? Ain't got a friend. My only sin is in my skin. What did I do to be so black and blue?” (Waller et al., 1929). By the late 1920s, Black Americans were experiencing a decline of the Harlem Renaissance brought on by the stock market crash and growing racial tensions. Some advancements in society occurred during this decade of artistic growth, while the barriers of segregation, race riots, and economic hardships continued. Additionally, the malice of lynchings persisted. In 1927, a political delegation from Harlem visited with the United States President Calvin Coolidge in the executive office to address the carnage. The New York Times (1927) reported that President Coolidge cited his ineffectiveness due to filibustering by southern Senators.

To appease the group, the President raised the possibility “of declaring martial law in a State where lynchings were rampant” (1927). Robert Nemiroff, music publisher and songwriter, framed the pragmatic mindset of Black Americans to defy these embedded obstacles with his writings about author Lorraine Hansberry and her “insurgency” to dismantle racism. He argued: “But if blackness brought pain, it was also a source of strength, renewal and inspiration, a window on the potentials of the human race” (Hansberry et al., 2011, p. xx).

In similar vein, Duke Ellington’s recording of “Black and Tan Fantasy” (1928) signified the African American social struggle through a celebration of Black and tan jazz venues that permitted racial mixing, “unlike the Cotton Club, which refused to admit blacks” (Giddins and DeVeaux, 2009, p. 141). In this composition, the muted trumpets and trombone, with their high and low intensities, are strikingly vocal-like conveying themes of suffering, struggle, and triumph. Newly featured and booked for three years at the Cotton Club (p. 140), Ellington’s composition served as an unassuming civil rights protest, allowing for an unpacking of racial inequality through a bluesy spiritual message to a Black and white audience. Both Armstrong and Ellington were depicting Blackness artistically to exert influence and agency as African American audiences navigated deeper “social and cultural complexities and change” (Baraka, 2002, p. 62). Their declarations were coded in musical tones, melodies, and lyrics. Armstrong’s phrases, such as “I can’t hide” and “My only sin is in my skin,” connoted the Black understanding of the marginalization experienced by a broad set of people by ranked skin color (Waller et al., 1929). These words, “combined through grammatical rules (syntactically) to form a mode of communication,” served as cultural language (Barnard and Spencer, 2012, p. 411). In his book Jazz: A History, Frank Tirro introduced the concept of a “grapevine telegraph” in early African drumming. He noted that messages “were sent from station to station in codes, some of them musical, that only initiates could understand” (1977, p. 32).

I Feel Like Shouting

To an equal extent, Black gospel songs possessed a vernacular of hope and salvation, for instance, minister and composer Charles Albert Tindley’s composition of “We’ll Understand It Better By and By”. The allegory beyond spiritual revival evangelized a coded response to the Black experience in America. Tindley (1905), employing the first person-perspective of “we,” narrated how his people were “tossed and driven” by a restless sea and howling tempest. This adversity, conceivably racism, gave way to deliverance through faith and trust in the Lord. Forty years later, with vivid and soul-shaking delivery, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson repeated the chorus “I feel like shouting” multiple times in her cover of “How I Got Over” (Ward, 1951). In conversation with bell hooks, Cornel West identified this “yet holding on” and perseverance ideology. West noted how African Americans, through jazz and the blues, responded “in an improvisational, undogmatic, creative way to circumstances in such a way that people still survive and thrive” (West, 1999, p. 544). Jackson paired her cry of suffering with rhythmic convulsions. William Banfield (2010, p. 152), in analysis of the “celebratory ritual”, characterized skillful moans, groans, and screaming in the vocal delivery. Gospel, blues, jazz, and rhythm & blues expressed tragedy and struggle with a counterbalance of optimism. This tradition of fortitude and having “feet on solid ground” was a unique Black agency born of the African slave trade and loss of ancestry, language, and tradition. From the shores of West Africa, Black Americans initiated rebellion in pursuit of their “fullest possible realization of human potentialities” (Dewey, 1989, p. 100). Strategic in these events was defiance by means of “a private language reserved for a subculture” (Tirro, 1977, p. 32).

In the 1960s, this call-and-response language became more conspicuous. “Say it loud, I’m Black and I'm proud,” a hit by musician and singer James Brown, added to years of resistance against racism and a continuance of Black messaging. Brown, wielding biblical references, preached a lengthy sermon diagnosing racial and economic inequality and promoting self-determination. In the first verse, where Brown sang “We’ve been ‘buked and we’ve been scorned, We've been treated bad, talked about,” he drew inspiration from early storytelling, infusing a contemporary tone (Brown and Ellis, 1968). “I've Been Buked and I've Been Scorned” was a traditional African American spiritual recorded by the Tuskegee Institute Singers in 1916. Brown’s version altered the lyrics of individual deliverance to reflect his vision of the redemption of Black people at the climax of the civil rights movement, having witnessed the assassination of minister and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. The chorus utilized call-and-response as Brown repeated, “Say it loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud).” Subsequently, as an urban griot, he petitioned the congregation with phrases like “Let me hear ya, ha” and more chants of “Say it loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” (Brown and Ellis, 1968). At other instances, Brown addressed the supreme being as “Lord,” “Lordy,” and “God,” merging spiritual and secular ideologies alongside an affirmation of Blackness. Brown transitioned from rhythm & blues into the revolutionary funk genre in the mid-1960s. Funk “used rhythmic contrast in innovative ways…was flexible and open-ended” (Giddins and DeVeaux, 2009, p. 535-6), satisfying the appetite of a younger, multicultural audience. Brown’s innovative adoption of spiritual strivings, including “the freedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, the freedom to love and aspire” (Du Bois, 2010, p. 12), into groove music was a key marker in the evolution of Black expressions.

A year later, Nina Simone sermonized “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” (1969), a song inspired by the play and book of writer Lorraine Hansberry’s life.

Commencing with a soft piano and choral arrangement that seemed to receive the choir, drums began to build in intensity as Simone’s voice narrated hardship with a remedy of Black love and authenticity. This protest song, delivered with repetitive instructional phrases and dramatic pauses, deflected conventional rhythmic patterns, elevating an emotional and unforgettable message. Much like James Brown’s imbuement of spirituality, an intact soul was Simone’s outcome to knowing and practicing being young, gifted and Black. The final emphasis in the song was conveyed through marching drums augmented by a lengthy, choral vibrato using the words, “Is where it’s at” (Simone and Weldon, 1969). Echoing the Afro hairstyles, berets, and leather blazers popularized by the Black Panthers, this song’s creed served as a conduit to consciousness and freedom. Ted Gioia (1998, p.337), in discussion of the intersection of postmodern jazz and the civil rights movement, noted that freedom was “a battle cry…a first principle on which all else depended.”

Black by Popular Demand

This ideology was promulgated at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States. HBCUs, as commonly referred, are defined by the United States Higher Education Act of 1965 as “any historically black college or university that was established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association” (U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2023). At southern HBCUs, like North Carolina A&T State University, Bennett College, South Carolina State University, and others, students inculcated the expressions “Black by popular demand,” “the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice,” and “it’s a Black thing you wouldn’t understand.” These enciphered phrases produced their meaning through the arrangement of words, reflection of events, and references to commonly held cultural truths. Stuart Hall’s exploration of signs in language posited that codes are crucial to convey such meaning. Additionally, Hall (2012, p. 29) identified that these codes are dependent on social structures and “shared ‘maps of meaning’—which we learn and unconsciously internalize as we become members of our culture.” This theory informed the way Black cultural expressions shared meaning beyond geographic and demographic boundaries. It is, then, the rendering of particular Black experiences into a cultural language that sustained and transformed over time. The phenomenon of cultural expressions thrived in the unique environment of HBCUs, where diverse students converged for training in black excellence and leadership, equally social independence from white majority culture. At the start of the twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois specified the function of the Negro college. “It must maintain the standards of popular education, it must seek the social regeneration of the Negro, and it must help in the solution of problems of race contact and cooperation” (Du Bois, 2010).

In 1929, Harlem Renaissance writer Wallace Thurman authored The Blacker the Berry, a tale of colourism that existed in the Black community since the transatlantic slave trade. Emma Lou, the dark-skinned protagonist, attempted to evade Black social societies that ranked and referenced skin color, only to encounter the malady everywhere she settled. In the end, her experiences, both external and internal conflicts, were a pathway to self-acceptance. The context of the motto came from Emma Lou’s romantic companion’s justification for dating her. He said, “Why not? She’s just as good as the rest, and you know what they say, ‘The blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice’” (Thurman 2020, p. 66). Over the years, this saying, removed of its sexual conquest and commodity animus, has ascribed a Black complexion or Blackness as having potent beauty, magnificence, and swagger. This proclamation of being “black–fast black–as nature had planned and effected” (Thurman 2020, p. 3) was clinched in the lingo’s adoption by HBCUs and its dissemination on apparel merchandise. In October of 1988, North Carolina A&T State University themed its homecoming “The Rare Essence of Beauty in Aggieland,” exemplifying unity and expressing togetherness. With similar sentiment to “the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice,” these words declared the school’s rarity and exceptionalism, not only in terms of Black aesthetics but also in scholarship and benevolence.

Black college students seized influential adages to signify their collective power at HBCUs and celebrate their generation’s music, art, and literature. Through alternative knowledge sources and evangelizing rap lyrics, Black students were guided to “reject the selfishness and individualism of the ‘Me Generation’ and confront serious life issues” (Kondo, 1987, p. ii). Academic achievement, professional engagement, cultural elevation, and political influence were adjacent to this grassroots Black philosophy. In The Black Student’s Guide to Positive Education (see Figure 1), a seminal book on the miseducation of Black people, the importance of collectiveness was stressed.

This is the task now before you, Black student. Put your people before yourself. Forsake individualism for peoplehood, me for us, individual aspirations for community aspirations. Make the sacrifices necessary to struggle for your people…but always know the language of your people. The language of your people is unique, legitimate and valid and is a cultural expression. It will always be in your best interest to be able to utilize it. (Kondo, 1987, p. 7-9)

While being ministered to seize language and redefine oneself as “Afrikan [sic]”, students were absorbing urban hip-hop doctrines and aesthetics on Black struggle, liberation, and advancement through the dopest lyrics and beats. Public Enemy’s release of Fear of a Black Planet in 1990 was paramount to this cultural uprising. In the song, power structures were challenged with freedom of speech, display of pride, mental toughness, and the identification of racists and racism. The hook element, “What we got to say?”, was the call-to-action urging listeners to respond with “Fight the power” (Ridenhour et al., 1989). With utilization of call-and-response technique, Public Enemy’s ritualized chants created social integration and musical improvisation. The merger of diverse thought, spirituality, historical scrutiny, and creative activity on these campuses elevated Black “interests, goals, objectives, values and culture.” (Kondo, 1987, p. 8)

Figure 1

Image of The Black Student’s Guide to Positive Education. Author’s personal collection. Photograph by Author.

It's a Black Thing

“It’s a black thing you wouldn’t understand” was an expression that thrived at HBCUs. In 1989 at North Carolina A&T State University, the student newspaper, The Register, asked the campus what the phrase meant to them (Largent, 1989, p. 3). Some of the replies include the following:

This statement refers to the struggle of African-Americans which is not over. To be black in white America is something that only the ‘people of color’ would understand. (T. Bowden)

This statement erects the historical consciousness of the white and black individual. It indicates the fact that the black man is the original man. He was here first. Do you understand? (D.S.P. Dark Skinned Posse)

It means no matter what color, origin, creed or sex that black is such a complex word…that no one will ever be able to copy, create, establish or destroy it. (L. Webster)

Furthermore, the idiom “young, gifted and Black” reappeared in tandem with “it’s a Black thing.” Graphic T-shirts appropriated Bart Simpson, the fictional character on the animated series The Simpsons, and transformed him into Black Bart, proclaiming “young, gifted and Black dude!” and “it’s a Black Bart thing you wouldn’t understand.” As shown in Figure 2, this grapevine of communication became material culture, representing aspects of identity and producing economic value. Another popular expression, “Black by popular demand,” was merged with popular fashion brands. T-shirts were emblazoned with “Black no need to Guess?” paying homage to Guess Jeans, founded in 1981 by Paul and Maurice Marciano. The localized dress paired with Black lingo saw greater adoption and commercialization through music and movies including School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), House Party (1990), and Malcolm X (1992). Cultural critique followed as seen in the editorial titled “Knowledge Lost: ‘X’-ploitation” in The Register at North Carolina A&T State University. The author debated the commodification and shallowness of the appropriated idioms, stating, “Every other person you see is wearing ‘X’ articles and to think that last year most of these people were wearing ‘Black Bart’ t-shirts”…is Malcolm X just a fad, or is there a genuine…interest in his teachings” (Williams, 1991).

Figure 2

Tee Shirt with Black Bart graphic. Author’s personal collection. Photograph by Author.

Despite elements of superficiality, a union of cultural knowledge, hip-hop music, and style defined a new Black consciousness. Rappin’, stylin’, and posin’ was an agency to proclaim this identity.

Of the latter, these decorative garments were transformed of original design intent from Levi’s, Gap, and Girbaud and adorned with Black aesthetics that affixed cultural value. This is clearly indicated in Figure 3, showing an artist’s storytelling on men’s jeans and the intermixing visuals of Afrocentricity, language, and capitalism. Analogous to hip hop culture, status symbols were accentuated on graffiti-art jeans. For example, the reference to BMW, a German manufacturer of luxury vehicles, implied the best quality. This creative movement was rooted in dynamic Black messaging. The vocabulary, “it’s a Black thing,” exemplified a cultural response of a people, still preaching, defying, and thriving. Equally, it was a pronouncement about the scarcity of Black representation in textbooks, film, television, and fashion.

Figure 3

Graffiti-Art Jeans and Africa Neck Medallion. Author’s personal collection. Photograph by Author.

Indifference of Blackness

For almost two hundred years, Black agency and representation in the fashion industry has been volatile, commencing with Elizabeth Keckley, a seamstress and dressmaker for Mary Todd Lincoln, and reaching the fashion house heights of Virgil Abloh, founder of Off-White and creative director of menswear for Louis Vuitton. There were significant breakthroughs in the 1970s with Scott Barrie, Stephen Burrows, Jon Haggins, and Willi Smith having greater visibility through retail platforms at Henri Bendel, B. Altman and Company, Bonwit Teller, and others.

In reflection of this time, Haggins, a fashion designer, performer, and journalist, noted that they “were doing our thing and making our fashion statements while the Black Revolution was happening across America” (Haggins, 2023).

Modeling while Black

Starting in the late 1980s, Black models like Iman Mohamed Abdulmajid, Naomi Campbell, Veronica Webb, Karen Alexander, Tyra Banks, and others gained first name recognition. Their images began to populate magazines, and their runway-walks garnered fans on CNN’s Style with Elsa Klensch and VH1’s syndication of Fashion Television with Jeanne Beker. Consumer recognition of models prior to this period had been restricted to magazines divided along racial lines, such as Vogue, Cosmopolitan, and Essence. Barbara Summers, fashion model, noted in her book Skin Deep that Black models experienced the persistent barrier of racism, obstructing their opportunities to book fashion shows, magazine covers, and beauty contracts. This environment stemmed from the belief by industry leaders that a Black model on the cover of a magazine would cause sales to drop. In 2002, The New York Times indicated a subtle shift away from this ideology for men’s and teen’s magazines due to influential music and sports celebrities. Still, according to the Times, “the unspoken but routinely observed practice of not using nonwhite cover subjects—for fear they will depress newsstand sales—remains largely in effect” (Carr, 2002). Defying this barrier was the greater expansion of Black influence in popular culture through music, film, television, and sports.

And the inescapable fact was that by the turn of the century the American mainstream would include a greater percentage of people of color…reluctant advertisers would eventually expand their marketing to include these majority minorities, and in the process employ an increased number of representative models. (Summers, 1998, p. 172)

Equally, there was an ebb and flow in Black representation on fashion runways. From the 1980s, expansion occurred through noticeable bookings of Black models by designers like Yves St. Laurent, Christian Lacroix, Gianfranco Ferré, and others. However, numerous seasons yielded a decline in Black representation, such as during the fashion trend years of grunge, heroin chic, and deconstructionism. The latter movement defined new forms of beauty through contorted and twisted garment designs worn by models expressing lethargy adorned by darkened eyes, pale skin, and disheveled hair. Absence of Black models often materialized when designers, fashion editors, and model scouts adopted geographical conformity in their hiring practices, making individuality obsolete. During certain seasons, Brazilian, Russian, and Belgian models reigned on the global catwalks. An analysis conducted in 2012 substantiated the imbalance of Black models at the top twenty New York City modeling agencies, excluding Elite and Wilhelmina. As shown in Figure 4, Black female models made up 4.9% of 1,213 women, while Black male models made up only 4.6% of 941 men. In a 2010 census of the United States population, “the number of people who identified as black, either alone or in combination with one or more other races,” was 42 million or 13.6% (Census.gov, 2012). Comparably, The New York Times reported on a lack of diversity among runway models, labeling it “Fashion’s Blind Spot”. The publication noted that Black models “accounted for only 6 percent of the looks shown at the last Fashion Week in February (down from 8.1 percent the previous season); 82.7 percent were worn by white models” (Wilson, 2013). Dodging of accountability was cited: “the designers say the agents don't send them black models, and the agents say the designers don't want any black models” (Wilson, 2013). Yet, the variance in proportion to the consumer marketplace dispelled the claim that agencies were incapable of scouting Black models for fashion shows and brand marketing.

Figure 4

Listing of Black Female and Male Model Percentages at Model Agencies in 2011 and 2012.

A period of Black progress in the American fashion industry was the success of the so-called urban or hip hop apparel brands. Their customers were described as “primarily young men who favor the loose, hip-hop inspired clothing that has become both an urban and suburban uniform” (Trebay, 2002). Brands like Cross Colours, Karl Kani, FUBU, Phat Farm, Mecca, and others represented this emergence of “from the streets” fashion, giving Black and Hispanic youth alternatives to Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and Nautica. Being “sold in 1,200 stores across the country with retail revenue of over $200 million” in 2002 (Trebay, 2002), the Sean John brand was achieving stellar volume in comparison to the $80 million that Cross Colours had earned in the early 1990s (McAdams, 1994). However, brands still faced the capriciousness and hidden hegemony in the American fashion industry. Ertis Pratt, Maurice Malone's Head of Sales, highlighted this issue when he declared in an interview with The New York Times, “They call you ‘hip-hop’, you get three stores…they call Tommy ‘fashion’, he gets 70 stores,” (White, 1996). Momentum could not be curbed as substantiated by FUBU, a hip-hop clothing company that means “For us, by us,” attaining a wholesale volume of $350 million in 1999 (Kaufmann, 1999). The founders asserted that the brand was designed for young urban men from a Black perspective but was not a “call to racial exclusiveness” (1999). Even so, ethnicity did influence a division along consumer markets in the fashion industry, as demonstrated by The New York Times (1999) when it posed the question: “Can a company sell to mainstream America and keep its homeboy appeal?” Regardless of the obstacles, hip-hop brands, earning collective sales over a billion dollars at the start of the century, joined past designers and models in challenging the industry for greater representation and equal treatment.

Modern Jim Crow

Gradual Black progress in American fashion was made from 1980 to 2010 with an increase in Black-led brands and Black employees in the industry. Patrick Kelly, Willi Smith, Patrick Robinson, Tracy Reese, Byron Lars, Kevan Hall, April Walker, and Jeff Tweedy (former CEO of Sean John) to name a few made advancements. Nonetheless, this momentum witnessed cultural indifference by American and European luxury brands in the twenty-first century. These actions are categorized here as being infused with a “Jim Crow” mentality. The term developed in the 19th century, representing the distorted image, culture, behavior, and language of Black Americans. Thomas Darmouth Rice, an American actor considered the father of Negro minstrelsy, popularized the practice of darkening his skin with burnt cork in performances dating back to 1820. The Washington Post reported that Rice, following the study of an older slave named Jim Crow, “made up precisely as the original…singing a score of humorous verses to the air-slightly changed and quickened-of the poor, wretched cripple” (Quinn 1895). Also, Jim Crow was the label given to oppressive laws in the southern United States that restricted the liberties of movement, worship, living, and voting for African Americans following the Civil War. Visual misrepresentations of Blacks utilizing the Jim Crow brand were steadily disseminated through published sheet music covers and media of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Blackface caricatures rendered African American men and women with thick, red, pouting lips, protruding eyes, slothful postures, and tattered clothing. In the 1850s, an entertainment review by The New York Times evidenced the performance style that was considered vile.

A blackened face, a ragged coat thrown of the shoulder, and a pair of elaborately patched trousers, with a shocking bad hat, first introduced Ethiopian minstrelsy to a New York public…the thing took at first, though it was voted low, and it continued to be low for some time. (New York Times, 1859).

First, the fashion industry experienced missteps of depicting cultures, including a Rabbi chic collection by Jean Paul Gaultier in 1993, a Chanel evening gown embellished with Muslim verses in 1994, and a 2014 RRL & Company advertisement by Ralph Lauren’s western-inspired brand that used historical images of Indigenous Americans during a period of forced assimilation. Then, starting in 2018, a series of occurrences contributed to a diversity, equity, and inclusion reckoning within the American fashion industry. Three brands produced insensitive merchandise. Having controversy with graphic text, H&M displayed on their ecommerce site a young boy of the African diaspora wearing a T-shirt printed with the words “Coolest monkey in the jungle.” Similarly, Prada’s figurines and Gucci’s turtleneck sweater appeared to draw upon blackface imagery, emphasizing large red lips on their products. Additionally, Burberry faced criticism for a hoodie with noose-style trim, which signaled associations to lynching and suicide. The Ralph Lauren company contributed to these blunders when it retailed a men’s chino pant with a Greek letter graphic of Phi Beta Sigma, an African American fraternity founded in 1914. With retailing on Ralph Lauren’s French platform, the product description stated, “these chinos feature symbol-like designs inspired by college secret societies” (Ralph Lauren, 2023). Finally, Marni’s photo shoot images were interpreted as symbolizing the commodification of Black bodies with the placement of a handbag layered on a nude Black body and the reflection of shackles upon a model’s feet.

In an offering of remorse, a Twitter post by Gucci asserted that the organization was “fully committed to increasing diversity throughout the organization and turning this incident into a powerful learning moment for the Gucci team and beyond” (Gucci, 2019). One year earlier as shown in Figure 5, Prada took an approach of nullification to their retailing of disputed merchandise. They stated, “Prada Group abhors racist imagery…they [figurines] are imaginary creatures not intended to have any reference to the real world and certainly not blackface” (Prada, 2018). Addressing the noose symbolism on Instagram, Ricardo Tisci issued an intimate testimonial seeking empathy. He expressed, “Those who know me well or who know my work will understand that any references I have used in my collections have never been driven by negativity…I listen, I learn, I improve and I believe in the power of love” (Tisci, 2019).

Figure 5

Listing of Select Racial Controversies by Brands in the Fashion Industry.

H&M and Marni issued apologies on social media that targeted the root cause of their mistakes and offered remedies. H&M stated, “It’s obvious that our routines haven’t been followed properly…we’ll thoroughly investigate why this happened to prevent this type of mistake from happening again” (H&M, 2018). With comparable messaging by Marni, they acknowledged “our oversights across the review process are unacceptable” (Marni, 2020). The brand stated that it would seek to engage “more voices and creators of color” resulting in a more diverse fashion industry (2020). The Ralph Lauren corporation, in a statement to Watch the Yard, a media company that digitizes Black college culture, ascribed improper supervision. They noted, “While we have a rigorous review process in place for all of our designs, this has prompted us to take another review of our protocols to help ensure that this does not happen again” (Watch the Yard, 2020).

W.E.B. Du Bois (2010, p. 8), an American civil rights activist, identified an external lens or “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” This higher consciousness that had been operated by Black people would need to be practiced by fashion brands for true inclusion and a pathway out of indifference.

Quest of Blackness

The central hub for understanding African American culture, often conjured when different racial groups have been offended, was the Black church owing to its central role in the battle for civil rights and racial equality. Du Bois (2020, p. 117) noted that “the Church often stands as a real conserver of morals, a strengthener of family life, and the final authority on what is Good and Right.” Conceivably then, Donna Karan, American fashion designer, sought a spiritual awakening for her business when she selected a backdrop of a choir for her diffusion line’s spring 1995 fashion show. The New York Times documented, “At a rousing DKNY show, a live gospel choir roused the fashion audience singing, ‘Are you ready for a miracle?’” (Spindler, 1994). Originally recorded by Patti LaBelle and Edwin Hawkins in 1992, the song, employing call-and-response patterns, prophesied a worshipper’s preparation and collection of a blessing. The newspaper further described “Sunday Best tea dresses” of the 1930s, accessorized with little straw hats, white gloves, and patent leather handbags. At the time, the inclusion of the choir in a secular setting was received gladly as a celebration of gospel culture and African American singers alongside the promotion of fashion.

HBCUs Trending

Years later, to overcome the acts of cultural indifference within the American fashion marketplace, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) became the El Dorado by brands for showing Black culture credibility. HBCUs have had a distaste of mainstream conformity. Through tribes, groups, regional clubs, and social classes, there existed divergence in thought, politics, religion, and aesthetics; yet a unifying thread of comprehending Blackness was woven among institutions. Companies have historically sought out these institutions for diverse perspectives, investment, and talent.

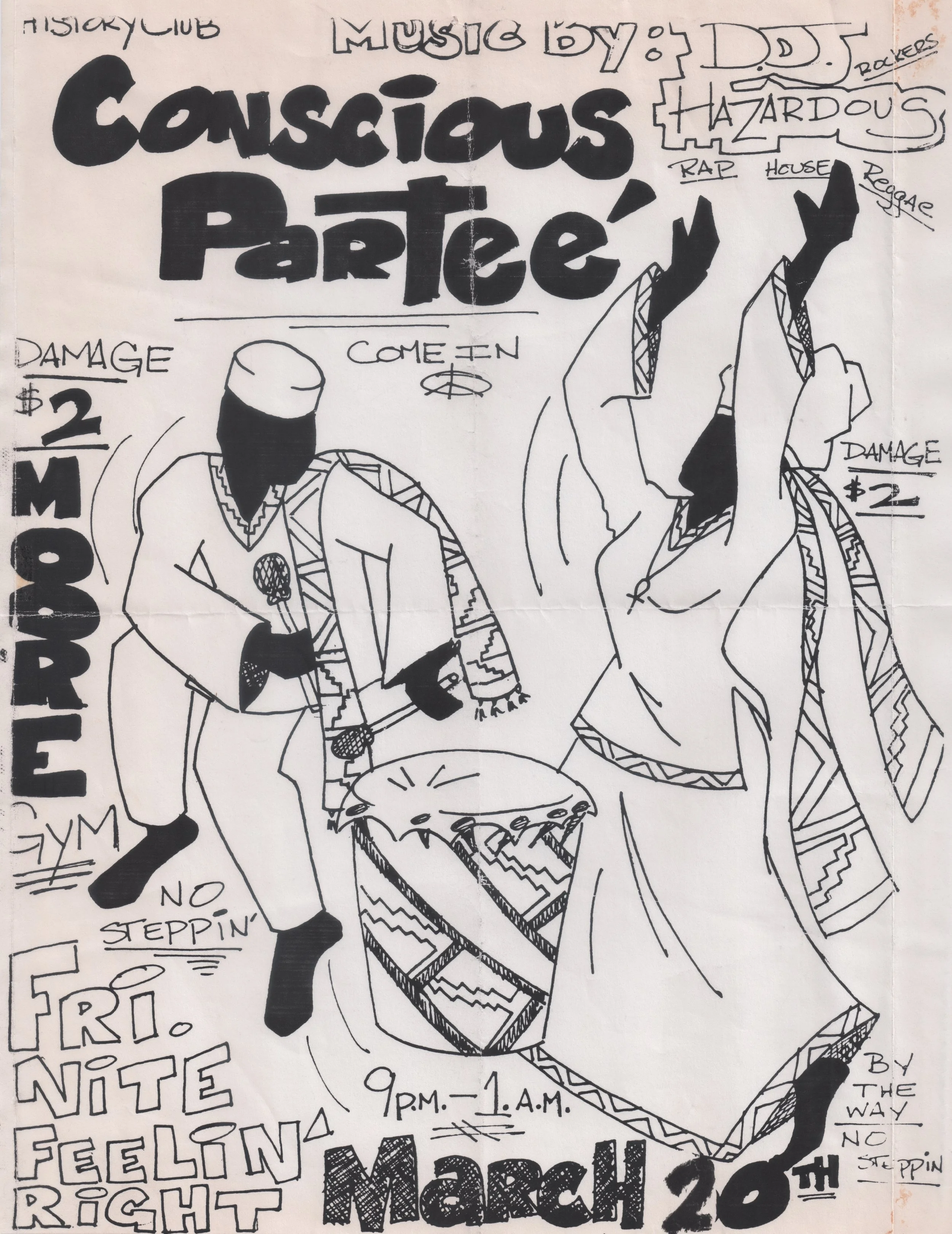

Furthermore, HBCUs provide an environment that promotes Afrocentricity, cultivating graduates with a consciousness of “defining, defending, and developing” themselves “instead of being defined, defended, and developed by others” (Kondo, 1987, p. 37). The Black Student’s Guide to Positive Education, Introduction to African Civilizations, Black Men: Obsolete, Single, Dangerous, and other non-conforming narratives have inculcated this wisdom. On campuses, the word “Black”, removed of oppressive negativity, was reclaimed as code for cultural membership, consciousness, and intellectualism. A promotional flyer for a social event at North Carolina A&T State University emphasized being conscious and wearing traditional African fashion for admission (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Conscious Partee´ flyer dated March 20, 1992 at North Carolina A&T State University. Author’s personal collection.

Most distinguishable in mining this Black cultural kingdom was the Ralph Lauren Corporation’s partnership with Morehouse College and Spelman College on a limited-edition apparel collection, film, and companion yearbook. Released for fall 2022, the idea was born from James Jeter, director of concept design and special projects at Ralph Lauren, who is also a graduate of Morehouse in 2013 (Mzezewa, 2022). The women’s and men’s collection featured traditional sportswear, active items, suits, and dresses with retail prices ranging from $20 to $2,498 (2022). A rich tradition of academics, sports, social networking, and dress heritage was expressed in the commemorative yearbook. The editors strategically placed sepia-toned images from both colleges’ annual yearbooks, dating from the 1920s to 1950s, adjacent to full- color contemporary images of models on the campuses. This technique blurred the lines between the present day and the past, showing that fashion and dandified aesthetics are timeless. Moreover, the use of historical imagery and nostalgic styling paired with the economic exclusivity of the collection’s merchandise superseded the extraordinary agency at HBCUs to elevate Black people through academic training, political discourse, athletic achievement, and praise of culture.

Conspicuously, elements of the Morehouse and Spelman yearbook evoke the visual and textual advisories of The Official Preppy Handbook published in 1980. This manual, a sarcastic guide to attending majority white Ivy League institutions, instructed legacies on respectable birthrights, prep schools, fashionable dress and language, and country club lifestyle. Within this handbook, edicts of preppiness were outlined stating, “Preppies inherit from Mummy and Daddy, in addition to loopy handwriting and old furniture, the legacy of Proper Breeding. Preppies soon learn that any deviation from the prescribed style of life is bound to bring disaster” (Birnbach, 1980, p. 18). With an exclusionary tone, fashion fundamentals were narrowed down to ten, including Conservatism, The Sporting Look, and Anglophilia. Readers were warned, “And although the Preppy Look can be imitated, non-Preps are sometimes exposed by their misunderstanding or ignorance of these unspoken rules” (1980, p. 121). The Ralph Lauren yearbook differs greatly from the Preppy Handbook. For example, it provides an attentive narration of “The White Attire Tradition” that carefully informs of the Spelman College custom with historical context. It explains, “The obligation for each Spelmanite to have a ‘respectable and conservative’ white dress was established around 1900…establishing a uniformed appearance among those present and denoting the significance of the occasion” (Ralph Lauren, 2022, p. 119). In his foreword, Ralph Lauren asserted, “Our portrait of American style, and our vision of the American dream, would be incomplete without Black experiences like this” (Ralph Lauren, 2022, p. 4). Lauren’s partnership with HBCUs, indicates a double-consciousness, newly practiced by brands for true inclusion and a pathway out of negligence.

With similar effort in his spring-summer 2014 fashion show, American fashion designer Rick Owens referenced the tradition of stepping, closely associated with Black fraternities and sororities at HBCUs. Solomon Northup, in Twelve Years a Slave, traced the ritual of stepping to the 1800s with its African traits from earlier times. He described it as follows: “The patting is performed by striking the hands on the knees then striking the hands together, then striking the right shoulder with one hand, the left with the other – all the while keeping time with the feet and singing” (Northup, 2010, p. 121). Titled Vicious, Owen’s runway presentation featured mostly Black female dancers modeling clothing while descending a metal staircase to a performance-runway floor. Wearing space age tunics embellished with bands of loose belts, the women of representative body types performed hard stepping while emoting ferocity. The powerful movements appeared as tributes and a ritual for battle, diverging from the call-and-response, spiritual intimacy, and evangelizing of early African American expression. In Shout Because You’re Free, the authors detailed the tradition as performed in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida by slaves and their progeny. They explained, “Then the ‘shouters,’ women dressed in long dresses and head rags of their grandmothers’ day, began to move in a counterclockwise circle, with a compelling hitching shuffle, often stooping or extending their arms in gestures pantomiming the content of the song being sung” (Rosenbaum et al., 1998, p. 2). Owen’s fashion embrace of stepping as a visual extravaganza of Black expressive culture admired and reimagined the style, albeit unaccompanied by enlightenment about its origins.

A final example in the quest for Blackness was evident in the Louis Vuitton Men’s spring-summer 2023 show, which began with a performance by FAMU’s (Florida A&M University) Marching 100. For HBCUs, the marching band along with the drum major were considered the rhythm warriors among students, representing the institution at sporting events and homecomings and evangelizing each school’s distinctive identity and unattainable spirit. Founded by Dr. William P. Foster, band director, the Marching 100 “pioneered a new style that entertained audiences with high-stepping, horn-swinging showmanship infused with Black culture and Black excellence” (Allen, 2023). Athletic games, often followed by one-on-one band competitions, were often won or lost based on the quality, harmony, and syncopation of the musical groups. Louis Vuitton went to the source of HBCU pride, transplanting the revered band to Carré du Louvre in Paris, France, paying homage to Virgil Abloh, American designer and Louis Vuitton artistic director of menswear. This creative vision of the marching band at a runway presentation had been “long-held” by Abloh, who passed away in the fall of 2021 (Skerritt, 2022). Although removed from a swaying football stadium in Tallahassee, Florida packed with students, faculty, parents, and alumni united in a sea of orange and green, the HBCU band spectacle was displayed to an audience on their terms, in the same way that Black jazz instrumentalists transported the American improvisation to European cafes and halls in the mid-twentieth century. It was stated that the band “electrified” the show at the Louvre (2022), and perhaps, imbued an informal education in Black tradition and representation accessed historically through civil rights and religious leaders. As companies and brands practice their cultural appreciation, diversity, and inclusion, the HBCU has become the nucleus. The Harlem Renaissance, a period of enthusiasm and patronage of African American arts occurring one hundred years earlier, warned of frivolity and frenzy. In Infants of the Spring, the author interrogated the effect of the phenomenon or delirium of “novels, plays, and poems by and about Negroes” (Thurman, 1992, p. 62). A character musing on the euphoria about Negro art declared: “And yet the more discerning were becoming more and more aware that nothing, or at least very little, was being done to substantiate the current fad, to make it the foundation for something truly epochal” (p. 62). This alert, with application to the quest of blackness by fashion brands, argued the prioritization of cultural literacy over spectacle.

Promotion of Blackness

Following the nationwide protests over the murder of George Floyd and the televised birth of the Black Lives Matter movement, corporations and institutions robustly expressed their stances on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Businesses declared alliances and publicized a long-term commitment to doing better. As discussed earlier, the American fashion industry had a poor record of racial inclusion among designers, fashion houses, and models. Bethann Hardison, former model and agent, objected to past efforts that were merely symbolic. Hardison noted: “The seemingly indifferent responses among companies to complaints of tokenism and lookism have become too insulting and destructive to ignore” (Wilson, 2013). More recently, The Kelly Initiative Group (2023), a coalition of Black professionals focused on equitable employment access in the fashion industry, declared that they are “committed to no longer allowing many of our best and brightest talents to go deliberately ignored, obstructed, or erased by the industry’s prioritization of optics over the authentic pursuit of equity.”

Blackout Day

One month after the Floyd killing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, DSW, the Designer Shoe Warehouse retail brand, proclaimed in emails and on their website: “In support of the Blackout Day 2020, we’re encouraging our customers to shop black-owned businesses today and every day” (DSW, 2020). Initiated by Blackout Day.org, the hashtag campaign challenged “1.5 million Black people, people of color and other supporters to avoid purchases online and in-store on July 7 unless it’s a Black-owned business” (Toone, 2020). Participants were directed to sign up online, post visual evidence to social media platforms, and desist from spending a dime unless Black-owned for 24 hours. Additionally, DSW’s campaign fortified its position, stating “It’s time for action. We stand with the black community and are dedicated to creating meaningful change” (2020). This assertive language—jeopardizing DSW’s revenues and profits—diverged from the feeble responses by fashion companies to improving racial diversity a decade earlier. Initially, organizations were calculated by choosing the term “Black” for a wide-ranging demographic. Black is more inclusive of people in the broader African diaspora than “African American” and “Black American.” Later, the designation of BIPOC, Black, Indigenous and People of Color, served a larger consumer market.

Barbershop Talk

Target Corporation’s “Black Beyond Measure” was another initiative launched after the outcry regarding police violence against African Americans. With locations across the United States, the general merchandise retailer, trademarked with the red and white bullseye logo, has been known for high-energy commercials promoting accessible lifestyle fashion. This diversity campaign, as well as the investment in Houston White, a Black apparel designer, developed from a meeting by Brian Cornell, Target CEO, with forty Black team members in a Black-owned barbershop in North Minneapolis. Here, with intimacy, Cornell heard from his team about their anguish and hopes. It replicated the African American tradition of barbershop talk where communal experiences and stories generate agreement, opposing ideologies, and comedic relief in a safe space. Cornell noted that the meeting with his Black leaders allowed him to “get to know them, understand some of the challenges they were facing, things going on in their minds but just spend that time connecting” (CBS Mornings, 2022). Since the 1960s, this visibility had been sought by Black designers and models for equal space at retail and on magazine covers, essentially leveling the playing field. Cornell’s earnest endeavors, years beyond the plight of Black designers, employees, and consumers to have representation, stimulated Target’s focus on Black entrepreneurship and supporting Black-owned or founded brands. Speaking directly to these groups, the retailer’s website communicates: “Your success knows no bounds. We’ve made a space for all of your ambitions, from the communities you uplift to the milestones you cross” (Target, 2023). In this pronouncement, a clear connotation of “space” is an area that is available or free to occupy. This has interpretation that the retailer created for an unspecified time a modification in operations to recognize and make visible these boundless Black aspirations. Perhaps, a more suitable statement using the language of The Kelly Initiative informs that Target will “invaluably enrich” its marketplace with Black talent and ambitions.

Nordstrom, an American luxury department store chain, executed a strategy to support and elevate Black-owned-businesses. The retailer quantified several marketplace ambitions: “We're committed to buying 10 times more merchandise from Black-owned or -founded brands by the end of 2030” (Nordstrom, 2023). Nordstrom’s website provided updates on the progress of initiatives that are inclusive of the Black, Hispanic, and Latinx populations. Statistics revealed that people of colour comprise 40% of leadership and 30% of the Board of Directors. Pertaining to diverse suppliers, Nordstrom (2023) noted the addition of 145 brands from three identity groups that collectively generated $175 million in sales. The retailer itemized their extensive plans to implement change within the organization, including interviews, workshops, meetings at all levels, and “a deep dive into data that helps us understand the makeup of our workforce” (Nordstrom, 2023). As Figure 7 shows, other retailers in America detailed their initiatives with inventive acronyms like SPUR (Shared Purpose, Unlimited Reach), STIP (Sephora Talent Incubator Program), and MUSE (Magnify, Uplift, Support, Empower).

Figure 7

Listing of Select Diversity Initiatives at Fashion and Beauty Retail Companies (retrieved from company websites in August 2023).

Challenging appearances of purely symbolic efforts, Nordstrom emphasized in its annual financial report that the company has “operationalized diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging through consistent reviews” (Nordstrom, Inc., 2023). The strategies and commitments for Nordstrom and other retailers have widened from delivering services, products, and experiences to “fostering greater representation of diversity” from all the communities that these businesses engage (2023).

Through publication of Holiday Style Heroes, a 2021 fashion gift guide, Amazon, an American multinational technology company, demonstrated inclusivity of BIPOC and other communities. Product descriptions, styling features, and storytelling merged with vivid photography of everyday heroes in their respective home locales. The fashion editorials featured Korean senior dancers wearing Fair Isle sweaters at a community services center, Native American activists adorned in printed and pleated apparel at Navajo Nation, and the Atlanta Drum Academy star students in Adidas activewear. These images transcended barriers by telling stories of diversity and inclusivity. Quotes of positivity such as “dress to your own beat, relax into your own rhythm,” “our time to shine,” and “the sky is the limit,” alongside merchandise, intertwined cultural appreciation with fashion, offering another pathway towards change for companies (Amazon, 2021).

These brief vignettes from a few large American retailers do not dispel claims of tokenism and calls for real change. The Oxford English Dictionary (2023) defines tokenism as “the practice or policy of making merely a token effort or granting only minimal concessions, esp. to minority or suppressed groups.” Fighting this insincerity and pursuing real accountability are organizations such as the Black in Fashion Council (BIFC), who targets systemic racist practices in the industry. The group declared, “For this change to occur, non-Black brands, publications, and people of influence have to carefully examine the roles they’ve played in either helping or hurting Black people who work in these spaces” (Black in Fashion Council, 2020). In 2021, #ChangeFashion was launched through a partnership with Color of Change (COC) and the Black in Fashion Council. The former organization’s mission was to address racial injustice and hostility particularly among corporations and government. This project yielded a road map resource with four recommendations including divest from police, invest in Black representation and portrayals, invest in Black talent and careers, and invest in Black communities (Lockwood, 2021).

The birth of other organizations, Harlem’s Fashion Row in 2007, Fifteen Percent Pledge in 2020, and Black Fashion Fair in 2020, demonstrated collectively, a revival of Black agency in the fashion industry. Black designers, brands, management, employees, and consumers are championed and elevated by the work of these groups. Markedly, this period dates one hundred years to the start of the Harlem Renaissance that generated visibility and passion for Black aesthetics through fine art, photography, literature, stage performance, and music. Both occurrences defined a set of shared experiences, judgments, and responses from being of African descent and living in the United States.

Liberation of Blackness

A course of amelioration has been shown in this exploration of Blackness. First, Black consciousness, with its vibrant history of language, literature, music, and dress, emanated from hardship and a battle for civil rights. The American fashion industry’s indifference to cultural experiences and challenges occurred over years, fed by a lack of diversity, inclusion, and organizational oversight. Different voices, expansive narratives, and authentic context were absent from certain corporate and management discussions. Third, literacy in the Black experience became a pillar to building both cursory and genuine inclusion. Historically Black Colleges and Universities were accessed as reservoirs for Black thought, culture, and aesthetics. Next, there was a pressing need for diverse talent, management, suppliers, vendors, and consumers, whom should be visible and heard through effective channels of communication. Lastly, implementing improvements that prudently bond cultural diversity and fashion commerce will have meaningful and measurable outcomes for both society and organizations.

In The History of Jazz, the final reflection on the music’s future having negotiated racially and politically charged periods, informed a conclusion regarding the fashion industry’s recognition of Blackness. Visibility, consciousness, agency, and defiance are just a few words that attempt to distinguish it. Blackness is ubiquitous, continually transforming, unable to be narrowed, confined, or concealed. In adaptation of Gioia’s (1998) words on jazz, it can be put forth that like the music, Blackness “of one people, then of a nation, is now a world phenomenon, and its history promises to become many histories…” (p. 395).

References

Allen, D. (2023). “The Legacy and Culture of HBCU Marching Bands”. July 19. https://www.bestcolleges.com/resources/hbcu/legacy-culture-of-marching-bands/ (accessed August 7, 2023).

Amazon (2021). Holiday Style Heroes. Fashion Gift Guide. Seattle: Amazon.

Banfield, W. (2010). Cultural Codes: Makings of a Black Music Philosophy: An Interpretive History from Spirituals to Hip Hop. Lanham: Scarecrow.

Baraka, A. (2002). Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Perennial.

Barnard, A. and Spencer, J. (2012). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Social and CulturalAnthropology. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge.

Birnbach, L. Ed. (1980). The Official Preppy Handbook. New York: Workman Publishing.

Black in Fashion Council (2020). “What is it like to be Black in fashion?”. https://www.blackinfashioncouncil.com/about (accessed December 30, 2023).

Brown, J. and Ellis, A. (1968). “Say It Loud – I'm Black and I'm Proud (Part 2)”. Recorded by James Brown. 5-1047 [1969]. Cincinnati: King Records.

Carr, D. (2002). "On Covers of Many Magazines, A Full Racial Palette is Still Rare". November 8. https://www.proquest.com/nytimes (accessed August 3, 2023).

CBS Mornings (2022). “Target Change: Target CEO Brian Cornell on Diversity, Inclusion, and the Economy”. September 7. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQjvNsqLuFw (accessed August 3, 2023).

Census.gov (2012). “Profile America Facts for Features”. CB12-FF.01. January 4. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features.html (accessed September 9, 2023).

CFDA (2022). “About Impact”, https://cfda.com/impact (accessed September 8, 2022).

Dewey, J. (1989). Freedom and Culture. New York: Prometheus Books.

DSW (2020). “4 Black content creators who inspire us”. July 7. Designer Shoe Warehouse. Email communication.

Du Bois, W.E.B. (2010). The Souls of Black Folks. Lexington: Readaclassic.

Giddins, G. and DeVeaux, S. (2009). Jazz. New York: Norton.

Gioia, T. (1998). The History of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gucci [@gucci] (2019). “Gucci Deeply Apologizes…”. February 6. Twitter. https://twitter.com/gucci/status/1093345744080306176.

Haggins, J. (2023). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. https://willismitharchive.cargo.site/Jon-Haggins (accessed August 3, 2023).

Hall, S. Ed. (2012). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

Hansberry, L., Nemiroff, R., & Baldwin, J. (2011). To be young, gifted, and black: Lorraine Hansberry in her own words. New York: Signet Classics.

H&M [@hm]. (2018). “We understand the many people…”, January 9, Twitter, https://twitter.com/hm/status/950680302715899904.

Kaufman, L. (1999). "Trying to Stay True to the Street". New York Times. March 14. https://www.proquest.com/nytimes/docview (accessed August 10, 2023).

The Kelly Initiative (2023). “The Initiative”. https://thekellyinitiative.net/ (accessed December 30, 2023).

Kondo, B. (1987). The Black Students Guide to Positive Education. Washington: Nubia Press.

Largent, N. (1989). The Register. September 29. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/ (accessed December 26, 2021).

Lockwood, L. (2021). “Color of Change, Joan Smalls, IMG and the Black in Fashion Council Launch #ChangeFashion”. Women’s Wear Daily. February 18. https://wwd.com/ (accessed December 31, 2023).

Marni [@marni] (2020). “At Marni, we are deeply apologetic…”. July 29. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDPtl8EHYAr/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=3d625d9d-b7b4-4e1c-9de5-916aadda9a3e (assessed August 9, 2023).

McAdams, L. (1994). “Loose Threads: Cross Colours was once the clothing label of choice for the hip hop crowd. But the company’s unraveling was as dramatic as its overnight success.”. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives (accessed August 3, 2023).

Mzezewa, T. (2022). "Ralph Lauren Goes Back to School". New York Times. March 29. https://www. proquest.com/nytimes/docview (accessed August 6, 2023).

New York Times (1859). “Amusements: Ethiopian Minstrelsy”. August 18. https://search.proquest.com/docview (accessed July 6, 2012).

New York Times (1927). “Report on Coolidge Visit: Harlem Negro Delegates Tell of Plea Against Lynching”. February 14. https://search.proquest.com/docview (accessed July 6, 2012).

Nordstrom (2023). “Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Belonging”. https://www.nordstrom.com/browse/diversity-at-nordstrom (accessed August 3, 2023).

Nordstrom, Inc. (2023). Nordstrom, Inc.: 2023 annual report 10-K. https://press.nordstrom.com/financial-information/sec-filings (accessed December 30, 2023).

Northup, S. (2010). Twelve Years a Slave: The Narrative of Solomon Northup. Ed. By C.S. Badgley. Lexington: Badgley Publishing.

Oxford English Dictionary (2023). “tokenism”. www.oed.com (accessed December 30, 2023).

Prada [@prada] (2018). “Prada Group Abhors…”. December 14. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Prada/status/ 1073614897207017481.

Quinn, E. (1895). “’Jumped Jim Crow:’ Reminisces of Rice, the Father of Negro Minstrelsy. An Original Dandy Darky”. Washington Post. August 25. https://search.proquest.com/docview (accessed July 6, 2012).

Ralph Lauren (2022). Polo Ralph Lauren Exclusively for Morehouse College and Spelman College. Special Edition Yearbook. Milan: Grafiche Milani.

Ralph Lauren (2023). Straight graphic chinos. https://www.ralphlauren.fr/fr/chino-graphique-droit-490931.html (accessed August 9, 2023).

Ridenhour, C., Sadler, E., Shocklee, H., and Shocklee, K. (1989). “Fight The Power”. Record by Public Enemy. ZT 42878. Hollywood: Motown and Universal Music Group.

Rosenbaum, A., Rosenbaum, M., and Buis, J. (1998). Shout Because You’re Free: The African American Ring Shout Tradition in Coastal Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Simone, N. and Weldon, I. (1969). “To Be Young, Gifted and Black”. Recorded by Nina Simone. 74-0269. Indianapolis: RCA Victor.

Skerritt, A. (2022). “FAMU Marching ‘100’ Band Makes Triumphant Paris Return at Louis Vuitton Fashion Show”. June 24. FAMU News. https://www.famu.edu/about-famu/news/ (accessed August 6, 2023).

Spindler, A. M. (1994). “Review/Fashion: Lots of Sugar, With Some Pinches of Spice”. New York Times, October 31. https://www.proquest.com/nytimes/docview (accessed August 6, 2023).

Summers, B. (1998). Skin Deep: Inside the World of Black Fashion Models. New York: Amistad.

Target (2023). “Black Beyond Measure”. Learn section, https://www.target.com/c/black-beyond-measure-learn/-/N-oetcy (accessed August 8, 2023).

Thurman, W. (1992). Infants of the Spring. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Thurman, W. (2020). The Blacker the Berry. Overland Park: Digireads.

Tindley, C. A. (1905). “We'll Understand It Better By and By”. Soul Echoes: A Collection of Songs for Religious Meetings, Edition 2. 1909. Philadelphia: Soul Echoes Publishing.

Tirro, F. (1977). Jazz: A History. New York: Norton.

Tisci [@riccardotisci17] (2019). I’d Like to Express…. February 22. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BuMTemZB_b6/ (assessed August 9, 2023).

Toone, S. (2020). “What is #BlackOutDay? Day organized for Black people to avoid online, in-store shopping”. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. June 30. https://www.ajc.com/news/what-blackoutday-day-organized-for-black-people-avoid-online-store-shopping/ (accessed December 30).

Trebay, G. (2002). "Fashion Statement: Hip-Hop on Runway". New York Times. February 9. https://www. proquest.com/nytimes (accessed August 3, 2023).

U.S. Government Publishing Office. (2023). “Higher Education Act of 1965”. GovInfo. https://www.govinfo.gov/ (accessed December 28, 2023).

Waller, F., Brooks, H. and Razaf, A. (1929). “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?”. Recorded by Louis Armstrong. Original Issue Okeh 8714. New York: Columbia.

Ward, C. (1951). “How I Got Over”. Recorded by Mahalia Jackson. KC 34073 [1976]. New York: Columbia.

Watch The Yard (2020). “Exclusive: Ralph Lauren Issues Statement to Watch The Yard Regarding their Phi Beta Sigma Pants”. January, https://www.watchtheyard.com/sigmas/exclusive-ralph-lauren-statement/ (accessed August 3, 2023).

West, C. (1999). The Cornel West Reader. New York: Civitas.

White, C. (1996). "The Hip-Hop Challenge: Longevity". New York Times. September 3, https://www. proquest.com/nytimes (accessed August 3, 2023).

Williams, G. (1991). The Register. October 25, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/ (accessedDecember 26, 2021).

Wilson, E. (2013). “Fashion's Blind Spot”. New York Times. August 8. Retrieved from https://www. proquest.com/nytimes (accessed December 29, 2023).

Author Bios

Alphonso McClendon, Associate Professor at Drexel University, researches the social, racial, and political intersections of African American history, jazz, and global influence. His publications include “Black by Popular Demand at HBCUs”, in Fresh, Fly and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style (Rizzoli 2023), Fashion and Jazz: Dress, Identity and Subcultural Improvisation (Bloomsbury 2015), “Hot, Cool and Gone in the Twenty-First Century”, in Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture (Intellect 2015), and “Fashionable Addiction: The Path to Heroin Chic”, in Fashion in Popular Culture (Intellect 2013). McClendon’s research has been conducted at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers, the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane, the National Museum of American History, and the Free Library of Philadelphia. He has been an invited lecturer at the Museum of Modern Art of NYC, the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, and Seoul National University.

Article Citations:

MLA: McClendon, Alphonso. “It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

APA: McClendon, A. (2024). It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand. Fashion Studies, 5(1), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

Chicago: McClendon, Alphonso “It’s a Black Thing, American Fashion Wants to Understand.” Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2024): 1-32. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050102.

Copyright © 2024 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)