Volume 1, Issue 2, #4 - 2019

Contemporizing Modesty

By ROMANA B. MIRZA

DOI: 10.38055/FS010204

MLA: Mirza, Romana B. “Contemporizing Modesty.” Fashion Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2019, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010204.

APA: Mirza, R. (2019). Contemporizing Modesty. Fashion Studies, 1(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010204

Chicago: Mirza, Romana. “Contemporizing Modesty.” Fashion Studies 1, no. 2 (2019): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010204.

Abstract:

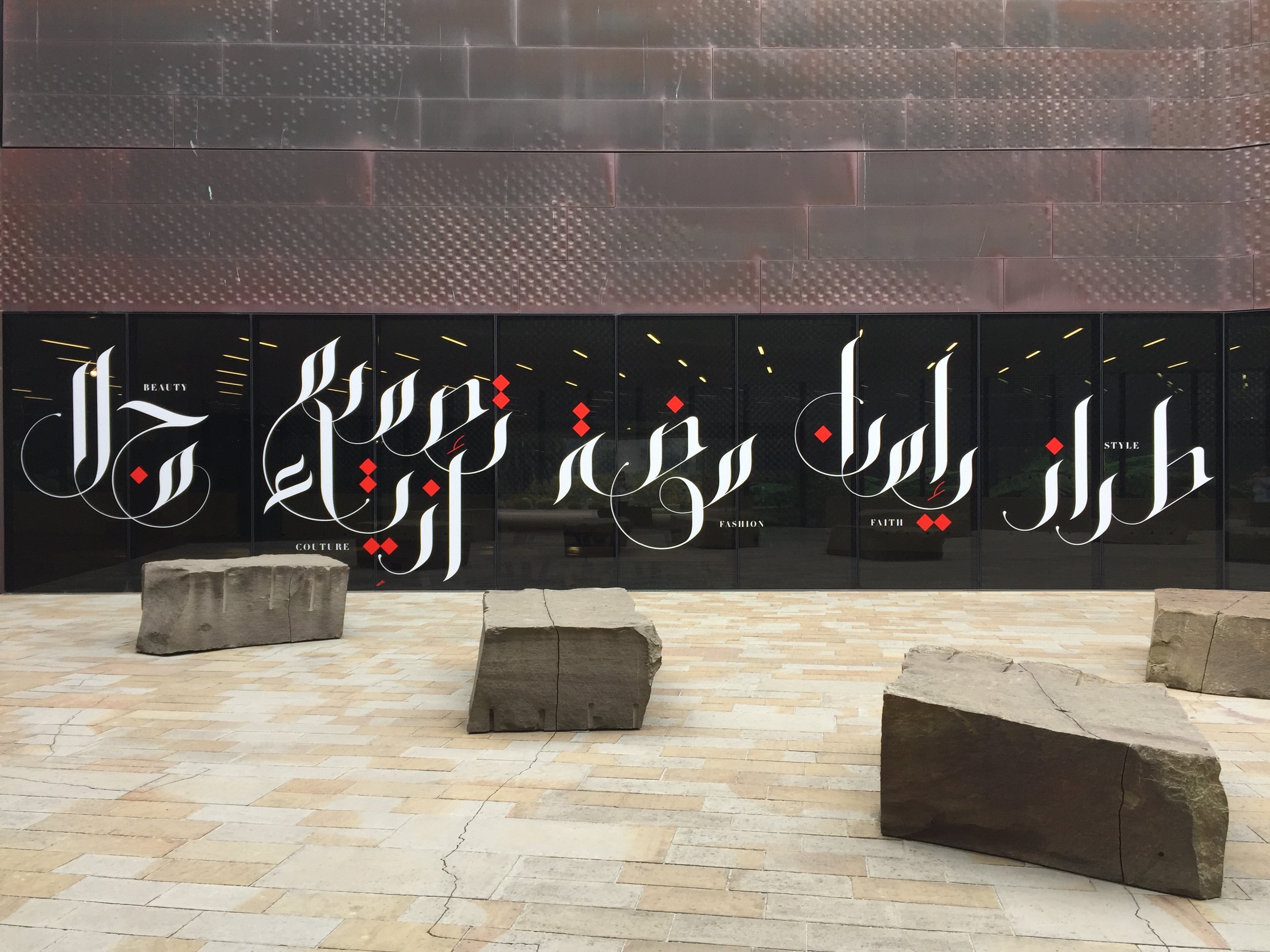

Contemporary Muslim Fashions, September 22, 2018 – January 6, 2019 was organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, shown in the de Young Museum and curated by Jill D’Alessandro and Laura Camerlengo, both curators at the museum, and consulting curator Reina Lewis, a scholar at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London. The aim was to represent contemporary Muslim fashions. To this end, they assembled and exhibited a collection of garments from the most popular fashion designers of the day, chosen from a series of shows at modest fashion weeks around the world. Supplemented by key pieces that have gained traction in the news such as the Burkini™ and Nike®’s sport hijab, this exhibit elevated perceptions and highlighted a global view by showing designs from around the globe, honouring the African-American, Muslim-American, Arab, and South East Asian cultures and aesthetics. Supporting the sartorial narrative was a display of visual and multimedia art from hip hop music videos, film, Instagram feeds, photography, magazine covers, and prints. The multimedia “exhibit within an exhibit” complemented the sartorial narrative by providing a contemporary context for the clothing. It reminded the observer that the exhibit was not merely about fashion history or the evolution of modesty in dress but about a contemporary moment. The relationship between fashion and the body was explored through designs that cover the body and intentionally hide the often objectified and sexualized female figure to reveal a contemporary approach to fashion that is empowering.

Keywords:

modest

fashion

exhibition review

multimedia