References

Alexander, M., Connell, L. J., Presley, A. B. (2005). Clothing fit preferences of young female adult consumers. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 17(1-2), 52-64.

Ålgars, M., Santtila, P., & Sandnabba, J. K. (2010). Conflicted gender identity, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in adult men and women. Sex Roles, 63, 11-125.

“America’s LGBT 2015 buying power estimated at $917 billion,” (2016). UTNewswire. Accessed April 19, 2017 from http://www.nlgja.org/outnewswire/2016/07/20/americas-lgbt-2015-buying-power-estimated-at-917-billion/.

Beemyn, B. G., & Rankin, S. (2011). The Lives of Transgender People. New York City: Columbia University Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-1010.

Brown, P., & Rice, J., (2013). Ready-to-wear Apparel Analysis (4th ed.). New York City: Pearson.

Catalpa, J. M., & McGuire, J. K. (in press). Mirror epiphany. In A. Reilly & B. Barry [Eds.] Crossing Boundaries: How Fashion Curates, Disrupts and Transcends Gender. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books.

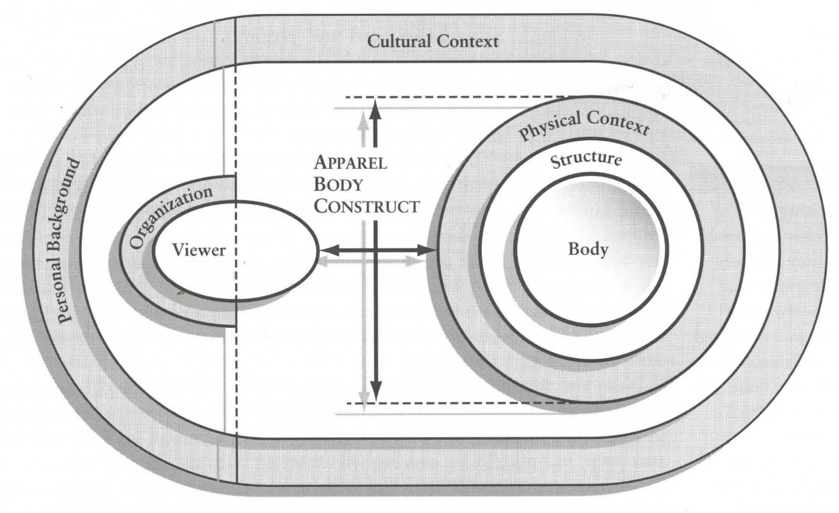

Delong, M. R. (1998). The Way We Look: Dress and Aesthetics (2nd ed.). New York City: Fairchild.

De Vries, A. L. C., McGuire, J. K., Steensma, T. D., Wagenaar, E., Doreleijers, T., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2014). Prospective young adult outcomes of puberty suppression in transgender adolescents, Pediatrics, 134, 696-704. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2958.

Dimock, M. (2018). Defining generations: Where millennials end and post-millennials begin. Pew Research Center. Available: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/defining-generations-where-millennials-end-and-post-millennials-begin/.

Doan, P. L. (2016). To count or not to count: Queering measurement and the transgender community. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 44(3-4), 89-110.

Eicher, J.B., & Roach-Higgins, M.E. (1992). Definition and classification of dress: Implications for analysis of gender roles. Oxford: Berg. Downloaded February 7, 2017 from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://hdd.handle.net/11299/170746.

Factor, R., & Rothblum, E. (2008) Exploring gender identity and community among three groups of transgender individuals in the United States: MTFs, FTMs, and genderqueers. Health Sociology Review, 17(3), 235-253.

Flores, A.R., Herman, J.L., Gates, G.J., Brown, T.N.T. (2016). How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. Downloaded February 7, 2017 from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf.

Gagné, P., Tweksbury, R., McGaughey, D. (1997). Coming out and crossing over: Identity formation and proclamation in a transgender community. Gender & Society, 11(4), 478-508.

Goldsberry, E., Shim, S. & Reich, N. (1996). Women 55 years and older: Part II. Overall satisfaction and dissatisfaction with fit of ready-to-wear. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 14(2), 121-132.

Hanks, K., Bellison, L., & Edwards, D. (1977). Design Yourself. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann.

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Jones, M. R., & Giddings, V. L. (2010). Tall women’s satisfaction with fit and style of tall women’s clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 14(1), 58-71.

Koberg, D., & Bagnall, J. (1981). The Universal Traveler: A Soft-systems Approach to Creativity, Problem-solving and the Process of Reaching Goals. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann.

Kurt Salmon Associates (2000). “Annual consumer outlook survey,” paper presented at a meeting of the American Apparel and Footwear Association Apparel Research Committee, Orlando, FL.

LaBat, K. L., & DeLong, M. R. (1990). Body cathexis and satisfaction with fit of apparel. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 8(2), 43-48.

Lamb, J. M., & Kallal, M. J. (1992). A conceptual framework for apparel design. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 10(2), 42-47.

McGuire, J. K., Doty, J. L., Catalpa, J. M., & Ola, C. (2016). Body image in transgender young people: Findings from a qualitative community based study. Body Image, 18, 96-107.

Morgan, S. W., & Stevens, P. E. (2009). Transgender identity development as represented by a group of female-to-male transgendered adults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(6), 585-599.

Otieno, R., Harrow, C., Lea-Greenwood, G. (2005). The unhappy shopper, a retail experience: exploring fashion, fit and affordability. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33(4), 298-309.

Park, S-M., An, E-J., (2014). Factors and clothing evaluation criteria on clothing satisfaction. The Korean Journal of Community Living Science, 25(3), 373-382.

Pfeffer, C. A. (2008). Bodies in relations — Bodies in transition: Lesbian partners of trans men and body image. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 12, 325-345.

Pisut, G., & Connell, L. J. (2007). Fit preferences for female consumers in the USA. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 11(3), 366-379.

Rudd, N. A., & Lennon, S. J. (2001). Body image: Linking aesthetics and social psychology of appearance. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 19 (3), 120-133.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. NewPark, CA: Sage.

Tamburrino, N. (1992). Apparel sizing issues, Part 2, Bobbin, May, 52-60.

Workman, J.E. (1991). Body measurement specifications for fit models as a factor in clothing size variation. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 10(1), 31-36.

Workman, J.E. & Lentz, E.S. (2000). Measurement specifications for manufacturers' prototype bodies. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 18(4), 251‐259.