Volume 2, Issue 1, #3 - 2019

Rethinking Children and Clothes

By Cecilia gomes

DOI: 10.38055/FS020103

MLA: Gomes, Cecilia. “Rethinking Children and Clothes.” Fashion Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS020103.

APA: Gomes, C. (2019). Rethinking Children and Clothes. Fashion Studies, 2(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS020103

Chicago: Gomes, Cecelia. “Rethinking Children and Clothes.” Fashion Studies 2, no. 1 (2019): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS020103.

Abstract:

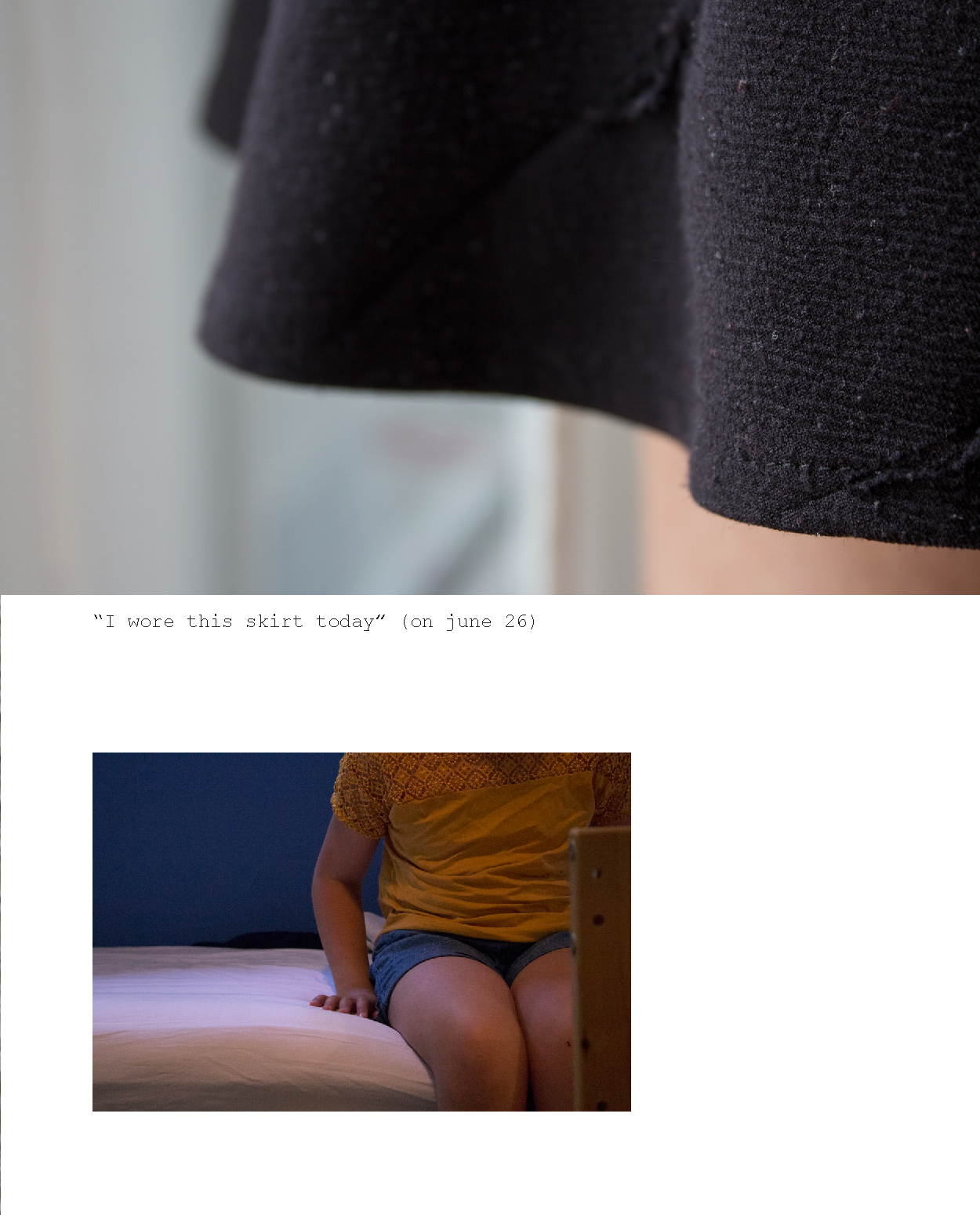

Rethinking Children and Clothes is a photo book designed to register the relationship children have with the garments in their wardrobes. I produced and photographed children in the intimate setting of their home, aiming to explore identity development during the transition from childhood into adolescence. Here, the clothes have emotional significance, durability that surpasses the physical integrity of the fabric. The photographs focus on the wear and tear, holes, stains, and rips that become part of much loved, worn clothing. The pictures show details of the dressed body, preserving the privacy of the subject but revealing aspects of their identity. Based on Sally Mann’s work with her family and discussions about children as research participants, this project is a conversation between fashion and childhood. I intend to propose a different way of seeing identity in a visual medium that is removed from identification. Additionally, the materiality of clothing, their “thing-power” (Bennett 348), demand their existence as objects of discourse between a child and society. The participants were invited to edit the final product and to share their thoughts in a brief interview. With this work, I suggest that wearing worn out clothing creates an emotional connection, preserving garments that do not have to be discarded or replaced so swiftly.

Keywords:

identity

children’s fashion

material culture

photography